Marvellous exhibition at the British Museum on the Japanese artist Hokusai. Real treat.

Read more in The New European

Marvellous exhibition at the British Museum on the Japanese artist Hokusai. Real treat.

Read more in The New European

Black art matters - of course it does - but was this the best way to make the case? I walked, I looked, I wondered…

Read more in The New European

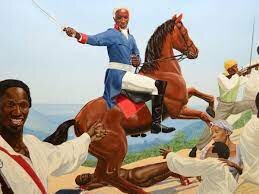

Touissant L’Ouverture at Bedourette by Kimathi Donkor

Larry Achiampong

Evan Ifekoya’s Ritual Without Belief

The walk from the mouth of the Thames, well, all right, from the flood defying barrier takes you through untidy London suburbs, shiny new - often empty - high rises and on into fields and floods. It has to be done. I managed it as far as Oxford spread over several months. Until I attempt the rest this marvellous set of images will more than compensate.

Prayers and play in Southend

When the 350th anniversary of the Mayflower voyage was celebrated in 1970 a spokesman for the Wampanoag tribe on whose territory the settlers had landed was invited to give a speech.

At the last moment he was excluded because the organisers ‘didn’t like what he had to say.’ He had planned to tell the world that the Wampanoag were part of the Mayflower story and should be recognised as such. And so they should. The tribesmen could easily have driven off the interlopers, half of whom died within five months of landing in November 1620, but instead, they made peace, they showed the settlers how to survive in that alien landscape, grow corn, catch fish and ensure their first harvest.

The long-delayed expression of their grievances was to be central to an ambitious ceremony planned for Plymouth, Devon, where the Mayflower docked briefly before sailing to America in September, 1620. Postponed last year and rescheduled for July 10-11 - only to be kiboshed again by Covid.

You would imagine universal disappointment at the news but not so. Take this acerbic tweet from @MayflowerLondon, one of the many significant players in the anniversary celebrations: ‘Great news that the awful M400 Ceremony has been cancelled. Focussing M400 celebrations on Plymouth Devon distorted the history of Britain.’

The reason for their hostility? For many - and for me who spent five years writing Voices of the Mayflower which is out now - the story has become, not about the Mayflower, not about the settlers, but about the Native Peoples.

The re-writing of history has been under way since that snub in 1970, shared and encouraged by the governing body, the General Society of Mayflower Descendants, and reinforced months ago when the original anniversary plans for the UK were announced.

Jo Loosemore, director of the Plymouth museum The Box, declared that the need to examine ‘difficult history’ was central to a ‘major exhibition looking at the controversial history of British colonisation.’ Myths would be debunked - though the publicity did not spell out what they were. She and Mayflower 400, the umbrella group organising events across the country, were advised by Wampanoag activist, Paula Peters, who described the collaboration as a chance to tell ‘a story that has been marginalised for centuries’.

But it is the Mayflower settlers who have been marginalised. More, many descendants, proud of their heritage, consider that the narrative of their ancestors’ audacious voyage has been hijacked.

The Box’s pre-pandemic publicity enthused about its exhibition, Mayflower 400: Legend & Legacy with its array of Mayflower-related artefacts but the headlines were about a Wampanoag ceramicist who was to make a cooking pot based on a traditional design and there was great enthusiasm for a ‘fully decolonised art and events programme’ presented by 29 Native American artists from New Mexico. (Not a destination on the itinerary of the 1620 voyagers).

Much was made of a wampum belt made of shells from the New England sea shore as a symbol of the spirit and culture of the indigenous peoples. What the publicity did not explain was that wampum, more prosaically, was used as a currency by Europeans and Native Peoples alike and as the settlers’ governor William Bradford wrote: ‘It makes the tribes hereabouts rich, powerful and proud and provides them with arms and powder and shot...’

That small piece of knowledge brings some balance to the inference that the Wampanoag culture was snuffed out by exploitative colonialists.

Nevertheless, the official position was that the Wampanoag had been ‘excluded from the narrative... despite having been devastatingly affected by colonisation due to the Mayflower's arrival and subsequent European settlement.’ The indigenous people ‘eventually saw their lands and homes brutally taken from them and ultimately the slaughter of their proud people.’

Well, let’s look at those statements. One claim is that disease spread by the settlers killed off the Native Peoples. Not so. It was spread by different explorers some three years earlier.

Devastatingly affected? When the settlers arrived the land was deserted. They did not fight for it, or seize it. Even years later, as the settlement in new Plymouth expanded its borders, they bought the land from the Wampanoag.

Paula Peters, the anniversary adviser, once declared: ‘The goal (of the Mayflower incomers) if not to annihilate was to assimilate (the Wampanoag)’ but there were negligible hostilities between the English and Wampanoag apart from a brief flurry of gunshot and arrows when they first landed. Furthermore both parties signed a peace treaty in March, 1621, which lasted for more than 50 years. It was only then that the all-out assault on the indigenous people began and it was led by a different group of settlers.

This idea of a colonising force, so casually bandied about, is preposterous when you realise that the Mayflower sailed short of weapons -‘nor every man a sword to his side,’ grumbled Bradford. Furthermore, the voyagers were made up of families with almost as many women and children as men on the ship. Not the most effective force to annihilate even the feeblest of foes.

So how have we reached this alternative version? It seems clear that centuries of justified rage at the genocide of their people, disgust at slavery - though there is no evidence that the settlers used forced labour - has been conflated and attributed to the settlers. And what better time than an anniversary to promote that message?

How was that anger, that need for reparation, to be reflected by Mayflower 400? Before Covid struck, plans had been made to hold an ‘unforgettable weekend (on July 10-11) of music and dance fusing hip-hop with an evening of live music, choirs and schools’.

Well, it might have been fun. It was also hilariously inappropriate. One can only imagine what Governor Bradford and his pious settlers would have made of it.

This was the man who sent a band of armed men to destroy a rival English settlement because they were ‘quaffing and drinking both wine and strong waters in great excess. They also set up a May-pole, drinking and dancing aboute it, inviting the Indian women for their consorts, dancing and frisking together.’ This is also the religious diehard who broke up a Christmas party because ‘there should be no gaming or revelling in the streets.’

He might have been perplexed by the Mayflower 400’s plans for Plymouth which have survived, including a giant puppet in the form of a dragon which is destined to roam through the city and distinctly unamused by a comedy play which considers important Mayflower-related issues such as, ‘why do our American friends call trousers pants?’

It’s not as if there cannot be fitting commemorations. Talks, walks and festivals are going on from Chorley Lancs, to Southampton, from Shrewsbury to Harwich, in Dorking and in Dartmouth. A flotilla sailed up the Thames recently on the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower’s return to Rotherhithe and in Scrooby, Notts, a festival will be held in the manor where many of the dissidents who inspired the pilgrims gathered in the late 16th, early 17th, centuries.

But the enterprising Bassetlaw Museum in nearby Retford has also been beguiled by the Wampanoag story and plans to demonstrate the building of a traditional Indian dwelling. Educational, interesting, but how about telling how the half a dozen able-bodied settlers managed to wrest homes out of the wilderness during the first winter as half their number fell dying amongst them?

But let’s not be spoil sports like the stern Bradford. What about the formalities - the speeches, the appeals to the core values of freedom, humanity, imagination and the future which were to be extolled during the revelries?

In the publicity, much was made of leading representatives of the Wampanoag taking part. All right and proper. But there was something - or rather someone - missing. Although, ‘high-ranking dignitaries’ were to speak, there was no mention of a Mayflower descendant being included, and despite me asking twice, no one was able to confirm that anyone from Plymouth, Massachusetts, home of the General Society of Mayflower Descendants, was attending. In fact, one leading light in the Mayflower community had made her own arrangements only to have her plans thwarted by quarantine regulations.

There are 30 million or so Mayflower descendants scattered around the world and a few thousand Wampanoag in New England. They both deserve to have their voices heard.

We know that Britain was the most enthusiastic colonial power when it came to slavery but others were not far behind in perpetrating this vile trade as an unflinching exhibition at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam demonstrates.

Paulus, the possession

The Oopjens

We’ve become so used to not going anywhere that it seems counterintuitive to suggest that now that the doors are opening we visit galleries virtually rather than in the flesh. But on the other hand…

There’s nowt so queer as folk and photographer Homer Sykes has proved that over the years. Here’s a jolly romp through curious customs which, surprisingly, continue to this day. Read more in The New European:

The Nutters!

The Marshfield Mummers

Drinks for the Burry Man

Areal-life tale as dramatic as Game of Thrones... with drama, fame, royalty, power, envy, retribution, and ultimately a brutal murder that shocked Europe. The murder of Archbishop Thomas Beckett commemorated in fine show at the British Museum .

The idea of paintings which you can smell was, er, not to be sniffed at. Here’s a piece on a show staged at the incomparable Mauritshuis in Den Haag, the Netherlands. In The New European, April 2021.

Read: https://www.theneweuropean.co.uk/brexit-news/europe-news/art-you-can-smell-7884712

Inevitably postponed by the pandemic this show at the Pallant, one of my favourite galleries, opened briefly only to be closed until… well, until when?

Meanwhile, read all about it.

Just what was it that made yesterday’s homes so different, so appealing?2004

Soft Pink….

The critic laughs

It can be Grimm in Gormenghast

This piece appeared online in the Daily Telegraph. It was due to appear in print but the new line up for Bake Off took precedence. The pilgrim mothers would have known how to cook honey cakes and make syllabubs but I don’t suppose there was much baking on the Mayflower.

Everyone has heard of the Pilgrim Fathers. Doughty, God-fearing souls who sailed to America on the Mayflower to create a world where they could follow their religious beliefs without fear of persecution.

But what makes the voyage remarkable are the mothers, the unsung heroes who sailed alongside their men on the momentous enterprise which began in July 400 years ago.

There were 18 women and of those, ten took their children with them. Incredibly, given the tumultuous adventure they were about to undertake, three were pregnant and another breast feeding her infant. Just as startling, there were more than 30 children and youngsters under 21 years old on the ship.

As for the men - the husbands, single men and servants - they totalled 50 in all and were actually outnumbered by the women and their offspring.

That the role of women in the story is scarcely acknowledged is perhaps unsurprising given that 17th century females invariably owed their status and identity to their men folk. Unsurprising too, that the accounts of the historic voyage are by men about the men, not least by William Bradford, who became governor of the new settlement in Plymouth, Massachusetts.

He did, however, acknowledge that the ‘weak bodies of women’ might not withstand the rigours of the journey though he could not foresee just how deadly the undertaking would be.

The arrangement was for the self-styled pilgrims to sail on the Speedwell from Holland where they had lived in exile from English persecution for 12 years and rendezvous with the Mayflower in Southampton. The Mayflower, meanwhile, left Rotherhithe, London, carrying 65 fortune seekers who had financed the expedition and hoped to recoup their investment by making their riches from the flourishing New England beaver trade. The two groups were to sail convoy across the Atlantic but the Speedwell became as 'leakie as a sieve’ and was abandoned in Plymouth, Devon, at which point many of the pilgrims joined the crowded Mayflower.

The ship, which had been used for the cross-Channel wine trade, now had 102 passengers thrust cheek by jowl in the stink of the hold, forced to endure the lack of hygiene, the smell of unwashed bodies and the grime of filthy clothes.

Privacy was impossible. To relieve themselves the voyagers had to balance precariously on the ship’s bowsprit but in storms they stayed below decks and used chamber pots which were sent flying across the cabins when the waves hit and the winds rose.

As for food; a niggardly diet of salt meat, peas, hard tack biscuits which became infested with weevils and to drink, beer. No wonder the hold became a breeding ground for lice and scurvy.

Not until the Mayflower dropped anchor off Cape Cod on November 11, 1620 - more than 100 days since leaving Southampton - were the women, at last, able to step on to land and wash their clothes ‘as they were in great need.’

Remarkably only one of their number died on the voyage but two soon followed after making land and a few weeks later Bradford’s wife Dorothy fell from the ship’s deck into the chill waters of the bay. Her body was never found. Strangely, Bradford records the death only in the appendix to his writings with a terse: ‘Mrs Bradford died soon after their arrival.’

Was he as indifferent as he seems? She was only 16 when they married and he 23 and she had been compelled to leave their three-year-old boy behind. Was she so desolate at being separated from him that she committed suicide? In truth, no one knows what happened that bleak winter’s day.

But what time could there be for private grief when cold, disease and hunger took away half the settlers in the first three months after landing? As they struggled to hew a settlement out the wilderness they were too enfeebled to resist scurvy - first the symptoms of putrefying ulcers and bleeding gums, then diarrhoea, fever and death.

The women suffered a far higher percentage of fatalities than the men or children. Only four mothers survived the first winter, not so much because of their ‘weak bodies’ but because the men were out in the fresh - if freezing - air, building their new homes, while the women were confined on the Mayflower for a further four months. In those close confines the disease spread quickly, especially as the women exposed themselves to danger caring for the sick and dying.

The death toll was remorseless. Of the pregnant trio who set sail, Elizabeth Hopkins, gave birth to baby boy Oceanus in mid-Atlantic, adding to the three children who sailed with her. Mary Allerton, who already had three children under seven, suffered a still-born birth and died within days. Sarah Eaton, who had been breast feeding her son, also perished, leaving the infant to be brought up by her husband.

And, as if in affirmation that among the saintly there are trouble makers, Eleanor Billington, who had two rowdy boys and years later witnessed the execution of her husband for murder, became notorious for her sharp tongue and was found guilty of slander, strapped in the stocks and whipped.

Perhaps no survivor had a more harrowing experience than Susanna White. Soon after the arrival she ‘was brought a-bed of a son which called Peregrine’ - the first child to be born in the new world and a brother to her five-year-old son. Her happiness was short lived for within weeks her husband William died. Yet on May 12, eleven short weeks later, she married fellow passenger Edward Winslow, a leading light in the movement, who himself had been widowed as recently as March 24.

Widowhood and remarriage were routine in those days of shortened life expectancy - of the 13 couples on the voyage four were second marriages - but this surely was no love match. Instead, they accepted that they had to sacrifice their own feelings for the good of the settlement which needed children to survive. Susanna had three boys and a girl. Her duty was done.

Of the four mothers left alive Mary Brewster, who at 52 was the matriarch of the new community, brought two of her four children. She was typical of a female who played a major part in the saga but is fleetingly mentioned while her husband William was - quite rightly - lionised as a pilgrim hero. But how much did he owe to the woman who supported him when they fled persecution in England in 1608 and through the years of exile in Holland? We are not told.

It was the generation of younger women who helped ensure the colony lived on. Six girls were orphaned in the first deadly winter and two were to marry fellow passengers. Their names, Elizabeth Tilley and Priscilla Mullins, are unknown to all but the most familiar with the Mayflower story but they had ten children each and their resilience and hard work were essential to the prospering of the settlement. Although there were other marriages and many more children, their legacy lives on in their descendants which include six US presidents.

All told 30 million US citizens can trace their heritage back to the Pilgrim Mothers.

Picture: artist’s impression of the first thanksgiving. Women doing all the work!

Voices of the Mayflower by Richard Holledge is out now

The eighth of a regular series of columns from the other side of the Atlantic discussing the people, places and events that led to the Mayflower voyage from an English perspective. The author’s novel Voices of the Mayflower is out now.

Today, Plymouth, Devon, the last port of call on the Mayflower trail.

Few places in England can boast of being home to as many buccaneering, swash-buckling adventurers as Plymouth.

Sir Francis Drake sailed the globe between 1577-1580 in a ship much smaller than the Mayflower, discovered California, ‘singed the king of Spain’s beard’ in a daring attack on the Spanish fleet in Cadiz and died attacking Puerto Rico in 1596.

Sir John Hawkins (1532-1595) was a naval commander, a privateer and a slave trader, Sir Ferdinando Gorges helped found Maine in 1622 and in 1616 it was explorer John Smith, not the settlers as many assume, who named the Wampanoag settlement of Patuxet after his home town - New Plimouth.

With such a gallimaufry of famous names strutting along the wharves it is hard to imagine the dockhands giving a second glance to the Mayflower and the Speedwell when they dropped anchor in Plymouth Sound in early September 1620.

Such are the quirks of history that if the Speedwell had not sprung yet another leak 300 miles out, the ships would never have come near the place. It scarcely registers with William Bradford who mentions its name once in his chronicle Of Plymouth Plantation but rather, concentrates his energy excoriating the skipper of the Speedwell and insulting troubled fellow pilgrim Robert Cushman.

Still, on this day tomorrow exactly 400 years ago (Sept 16) ‘They put to sea again... with a prosperous wind,’ and as the Mayflower sailed off into the horizon Plymouth, quite by chance, was able to add another name to its roll call of the illustrious - and the notorious.

Like everywhere involved in Mayflower 400 Plymouth has postponed its commemorative events until next year but it can boast an ambitious new museum, the Box, which is due to open on September 29.

Strikingly built of steel, glass and concrete it has been fused with the former City Museum and a church and will house permanent collections - including ship figureheads, a mammoth and, with a pleasing whimsy, Gus Honeybun, a puppet rabbit who was the symbol of the local TV station for 30 years.

This year the museum opens with an exhibition entitled Mayflower 400: Legend & Legacy. Three hundred items will elaborate on the lives and heritage of the passengers with a selection of 17th century drawings and diaries. Poignantly it will display the last known record of the Mayflower which describes the ship as being 'in ruinis' and values it at £128 8s 6d.

Above all, according to its press release, The Box aims to ‘debunk some of the myths surrounding the voyage’ and though the statement does not specify the myths it is exposing the exhibition has an emphasis on the impact of colonisation on the indigenous Wampanoag tribe by telling stories ‘of persecution, loss and oppression.’ It has become a familiar take on the Mayflower saga and one I wrote about a while back:

https://www.theneweuropean.co.uk/top-stories/story-of-the-pilgrim-mayflower-voyage-1-6738691

In pride of place, a pottery pot based on traditional design by the Wampanoag artist Ramona Peters and a beaded wampum belt, made from the purple and white shells of clams and whelks which celebrates tribal history and culture and imbued with an almost mystical significance. What is not mentioned is the importance of the beads as a currency used for trading with the Wampanoag. As Governor Bradford wrote: ‘It makes the tribes hereabouts rich and powerful and proud...’

The Box will be an asset to the city which relies heavily on the tourist trade. The place suffered grievously in the war when the heart of center was devastated and was rebuilt in the 50s and 60s. Old streets and buildings were swept away and replaced with car-friendly thoroughfares and frankly, monotonous architecture, which is relieved today by a shopping mall which won the Carbuncle Cup awarded by a building magazine ‘for crimes against architecture.’

I worked in the city as a young reporter and my lack of enchantment with the place was always blown away by striding along the wind swept Hoe, a sweeping sward high above Plymouth Sound. In pride of place, Smeaton’s Tower, a red and white striped lighthouse which was built on a reef 14 miles out to sea until the foundations eroded and it was brought to shore brick by brick. The view from the newly-restored lantern room stretches from the bleak hills of Dartmoor to the north and way out to sea.

At the eastern end of the Hoe you’ll find The Royal Citadel, a mighty bulk from the 17th century which replaced a fort built by Drake and funded by a decree of Queen Elizabeth I with a tax on the export of pilchards.

Below the citadel are cobbled streets and the busy little harbour but in my day I headed for a second hand book shop crammed to the rafters with frayed classics and paperback pot boilers and, miracle, it’s still there. I confess I had no interest in the Mayflower and unaware, for example, of the Elizabethan House, typical of a merchant’s dwelling from the 1500s which has been restored for the 400th anniversary as a museum - all beams, blackened fireplaces and wobbly furniture. Its gardens are a delight of beds filled with 17th century fruits, herbs and vegetables.

One of the older buildings is Island House which, according to Wikipedia is known as ‘the last place of accommodation for the Pilgrim Fathers on English soil.’ Apart from that irritating reference to Fathers - as most know, at least half the passengers were women and children - how can any know that they stayed there. I was corrected by a reader in no uncertain terms a few months back when I suggested the passengers might have disembarked. It was, he knew for a fact, that they did not leave the ship.

Today it is an ice cream shop selling exotic combinations such as cherry and custard, something the voyagers would probably not have enjoyed. Or maybe they did. Ice cream was first licked in China in the second century B.C and King Charles I (1625-1649) was fond of ‘cream ice.’ More like they had to settle for that delicacy, the ‘very silly small fishe,’ the pilchard.

Just across the road, framed by Doric columns, the Mayflower Steps from where our travellers are supposed to have embarked. The original Steps have long been covered by a road and, in fact, local historians reckon they were on the other side of the road near a Victorian public house, the Admiral MacBride. (Decent pint).

Who knows whether the voyagers used them. Rather like Plymouth Rock on which young pilgrim Mary Chilton might - or might not - have stepped so daintily when the Mayflower dropped anchor on a cold December day in 1620 they have both become part of the Mayflower tradition.

Steps and stones; fiction and fact. The story of the Mayflower.

This month’s Wicked insult: Fondling fop. Fondling, much-loved or petted person.’ Fop, a man overly concerned with his clothes and appearance. Medieval English, a fool. So, spoilt brat.

Info: Mayflower400UK.

Side trips to history: Cotehele is a medieval mansion with a working mill and glorious gardens on the banks of the River Tamar. Buckland Abbey built for Cistercian monks 700 years ago, home to Francis Drake.

Drink: The Plymouth Gin distillery, once a monastery, gives guided tours and encourages visitors to make their own cocktail.

Eat: Jacka Bakery, Southside Street, one of the oldest bakeries in the UK. Duttons Café Continental, high above the Sound. Fish and chips and mushy peas. Got to be done.

Stay: 16th century Boringdon Hall Hotel just out of the center. Atmospheric, as you’d expect from a hostelry which hosted Queen Elizabeth 1.

Voices of the Mayflower is out now.

August 1620. The Mayflower and the leakie Speedwell have left Southampton. They are on their way to the promised land. Or are they?

The seventh of a regular series of columns from the other side of the Atlantic discussing the people, places and events that led to the Mayflower voyage from an English perspective. The author’s novel Voices of the Mayflower is out now.

Today the trail takes us to Dartmouth, Devon.

For US readers: https://kingston.wickedlocal.com/news/20200816/voices-of-mayflower-dartmouth-by-sea

For the UK: Here’s the piece.

‘Our voyage hitherto has been as full of crosses as ourselves have been of crookedness.’

So lamented Robert Cushman, a leading light among the pilgrims, when the Speedwell, carrying the families from Leiden, sprang a leak 100 leagues out in the Atlantic and had to retreat for repairs to Dartmouth, Devon. In her wake, the Mayflower.

This was not a happy moment for the voyagers. They were beset with wrangles among themselves over misspent money and missing supplies. Many of them were frightened by the thought of sailing any further in the sieve-like Speedwell. ‘An infirmity has seized me,’ wrote Cushman on August 17, 1620, ‘It is as it were a bundle of lead crushing my heart.’ (Note he used the Julian calendar, roughly ten days behind today’s dates).

Despite his fears and frustrations, Dartmouth was an ideal port to carry out the repairs. Everything about the place then - and now - is about the sea, the ships and the seafarers.

It is one of the delightful of all the places on the Mayflower trail, with medieval houses tumbling down hills to the water front, narrow streets, pretty shops selling things you never knew you wanted, all against a tableau of yachts surging through the waves or bobbing gently in the watery enclosure known as the Boatfloat.

For a small place Dartmouth has had more than its fair share of history. It was recognized in the Domesday Book of 1086 - the record of everyday life in England - though the Celts and Saxons were in the area many years before.

In the 12th century mighty fleets sailed from Dartmouth to the Holy Land on the crusades, those stirring escapades both valorous and vainglorious in which the Christian world attempted to wrest Jerusalem from the clutches of the ‘infidel.’

In the early 14th century a swashbuckling figure, John Hawley, who combined being mayor with the more profitable role of pirate, led a motley bunch of volunteers to fight off an invasion by 2,000 Frenchmen and built the fortalice, or coastal fort, which today tands sentinel at the mouth of the River Dart, albeit in a tumbledown state. Eleven ships sallied forth to destroy the Spanish Armada in 1588 and one Sir Humphrey Gilbert who lived in Dartmouth sailed north to colonise Newfoundland.

And then, in August 1620, the two ships of our story dropped anchor off Bayards Cove. There is much conjecture as to whether the passengers disembarked while the repairs to the Speedwell were being carried out. Would they have stayed cooped up on board for eight or nine days? Surely the sailors stepped ashore for some R and R in the Cherub tavern and some suggest that the pilgrims climbed one of the hills overlooking the port to pray. As so often in the Mayflower story we can choose our own myths.

One thing is for sure; they would recognize many of the buildings. The local organizers of Mayflower 400 have arranged three trails which the careful, socially distanced, visitor can follow using an app which directs them up each narrow street, round corners and along the palm tree lined water front.

Better though, find a guide as knowledgeable and colorful as Les Ellis. He greets you in the red tricorn hat, red uniform and gold waistcoat of the town crier and walks the streets expounding on the history, the quirks and the fascinating corners such as Bayard’s Cove Fort, built between 1522 and 1536, where heavy guns were positioned to defend the town from attack; the Butterwalk in Duke Street, a Tudor covered way that was built to protect the dairy products sold there from the sun and rain. Today it houses a museum which might re-open in September with an exhibition on Mayflower. The Brown Steps, or Slippery Causeway, named after the color of the cobbles, which was once the pack horse trail and improbably, given how narrow it is, the main road into town.

He, and the several other volunteer guides united by a love for the place, explain how St Saviour's church in the lower town was built down on the foreshore because parishioners hated the struggle up the hill to the parish church of St Clement. It is considered one of the most beautiful 100 churches in England and St Petroc Church, first mentioned in 1192, one of the oldest though it was rebuilt after the Mayflower’s stay in 1641.

Of course, no port would be without is red light district and here it is in King’s Quay, a nondescript alley, barely 100 yards long. It used to be known as Silver Street because returning sailors would be paid in silver and promptly spend their earnings on women and beer.

Mr Ellis lent his voice to the unveiling last year of a new sculpture, ‘Pilgrim’ which is made of steel with bronze panels designed by local schoolchildren. His outstretched hand shields his eyes as he gazes out to sea to the brave new world beyond.

There’s another memorial American visitors might want to visit - and a melancholy one at that. Nearby is Slapton Sands a glorious stretch of shingle beach which was used by US troops to rehearse the D-Day landings because it was similar to the Normandy invasion beaches of World War 11.

In April, 1944, fast moving German E boats were in the English Channel and stumbled on US landing craft on maneuvers. Warning messages never got through and within minutes, two landing craft, which had been loaded with gasoline and explosives, were blown up. Hundreds of men perished instantly and those who managed to stumble ashore were, some claim, mistaken for the enemy and killed in friendly fire.

As many as many as 1,000 GIs lost their lives and the affair was hushed up for years. Today, however, a Sherman Tank stands on the beach with a plaque reading: ‘their sacrifice was not in vain.’

Is it too fanciful to think that some of those GIs were among the millions descended from the Mayflower voyagers?

Info:

Dartmouth Mayflower 400. Leslie Ellis +44(0)1803845501.

Getting there: Train from London Paddington to Paignton, Devon, then hop on a steam train along the coast to Kingswear and take a ferry across to Dartmouth. Knowing that Agatha Christie, the creator of Hercule Poirot, lived in Dartmouth adds a whiff of Murder on the Orient Express to the trip. If only because of the smoke.

Stay: The Royal Castle Hotel on waterfront. All sloping floors and thick walls, its 25 rooms are comfortable and stylish, lovely views of the river. It used to be two merchants’ houses joined together, and the main door is where the horses used to go through to the stables. Bayards Cove Inn. Timber-framed Tudor inn on the cobbled quayside has only seven rooms and a casual restaurant. A joy.

Eat: The Angel on the Embankment has Michelin star; Alf Fresco, Lower Street, the place for veggies; Rockfish, Embankment, for sophisticated fish and chips. Dart To mouth Deli on Market Street for prize winning cream teas. (To preserve your street cred in Devon, make sure to split the scone in two, cover each half with clotted cream and then add strawberry jam on top. In Cornwall 34 miles away it’s the other way round).

Drink: The Seven Stars, Dartmouth’s oldest pub and The Cherub, dating back to 1380.

This month’s Wicked insult: scurvy sneaksby. Scurvy, a worthless or contemptible person. Sneaksby, an insignificant or cowardly person, a sneak.

Pictures: artist’s impression, the Butterwalk, town crier Les Ellis.

The sixth of a regular series of columns from the other side of the Atlantic discussing the people, places and events that led to the Mayflower voyage from an English perspective. This month as the Mayflower replica glides home triumphantly we visit the London port where the original began its voyage.

The author’s novel Voices of the Mayflower; the saints, strangers and sly knaves who changed the world, is out now.

‘Near to that part of the Thames on which the church abuts Rotherhithe... there exists the filthiest, the strangest, the most extraordinary of the many localities that are hidden in London...’

So wrote Charles Dickens in Oliver Twist as he set the scene for the terrible denouement when the evil Bill Sikes tries to escape the vengeful mob by jumping from a house overlooking the filthy waters of the Thames but slips and hangs himself.

In typically bravura style adjectives and adverbs jostle to capture Dickens’s disgust at the ‘desolation and neglect’ of a part of London which for centuries was 'a hamlet where there is and long hath been a dock and arsenal where ships are laid up, built and repaired,’ as a 17th century account had it.

Dickens was writing in 1838 but it’s easy to imagine that 240 years earlier when the Mayflower lay at anchor preparing to make its momentous voyage in July 1620, the place would have been just as grim. A maze of narrow, muddy streets, thronged by ‘unemployed labourers of the lowest class, brazen women, ragged children, and the raft and refuse of the river.’

This was home to the skipper of the Mayflower, Christopher Jones, and his first mate, John Clarke and it was on long-gone wharves that the Mayflower used to unload its cargoes of wine from Bordeaux. In fact, in May of 1620 it had sailed in with 50 tons of wine for a wealthy importer.

What remains of those days? Like many of the villages and towns that we have visited on the Mayflower trail, sadly, next to nothing, but that’s not to say this part of London is not steeped with maritime history.

Its name derives from the Anglo-Saxon era (410 - 1066) with Rethra meaning a sailor and Hythe, a landing place. In 893 King Alfred granted land at ‘Rethereshide’ to an archbishop. He is the English king best known for hiding in the home of a peasant woman when on the run from the Vikings, letting his concentration slip and allowing her cakes to burn. It’s one of the first stories we learnt as school children - a bit like Washington and his cherry tree.

The docks date back to the early16th century and earned royal approbation in 1605 when the shipwrights of England were incorporated to maintain King James’s ships and barges, which were 'slenderlie and deceitfullie' constructed.

The shipbuilders, the caulkers and carpenters, were kept busy - but poorly paid - right up to World War Two when the area was flattened by German bombers. By then the docks were doomed. Because of bigger vessels and containerisation, trade shifted down river to the mouth of the Thames and the last ship left in 1970.

Today, what we find is more gritty than pretty. The simplest and most interesting way to get to know the area is to follow the Thames Path, which you can pick up anywhere along the river in the city. The organisers of the anniversary, Mayflower 400 have produced a nifty app which goes from site to sight.

Where to start? The Mayflower Pub claims to be near where the Mayflower was fitted out - though as with so many Mayflower myths and legends no one knows for sure. In 1620 it was called the Shippe Inn and rebuilt as the Spread Eagle and Crown in the 19th century. War damage led to a major refurbishment in 1957 so its cozy wood paneled bar is not as olde worlde as it seems.

Across the road is St Mary’s Church which was built in 1716 to replace a 12th century version and it is here that skipper Jones who died in March, 1622, is buried in an unmarked grave with his first mate John Clarke nearby.

Near the church yard is a strange looking sculpture dedicated to Jones which depicts St Christopher, looking back towards the Old World, carrying a child looking forward to the New while round the corner from the pub is whimsical statue The Sunbeam Weekly and the Pilgrim’s Pocket which has a newsboy in 1930’s dress, reading a newspaper telling the story of The Mayflower and all that has happened in America since. The pilgrim is reading the paper over the boy’s shoulder, looking astonished at how the world has developed since 1620. Well he might!

Now a stroll along cobbled streets and alleyways which in Dickens day were full of ‘offensive sights and smells, stacks of warehouses, tottering house fronts, dismantled walls, chimney half crushed’ but today have been replaced by 19th century granaries and warehouses converted into apartments and smart offices.

A mere half a mile upstream we reach the Angel. It is just as likely - maybe more so - that the pub was the watering hole favored by the Mayflower’s crew as they waited to sail to New England but the original has long gone though it does claim fittings from the 17th century.

Like the Mayflower Pub it’s a real pleasure to sit by the waterside, watching the mudlarks with their metal detectors searching for old coins on the muddy but optimistically named Bermondsey Beach and count the tourist boats and tugs chug by. It serves a decent pint too.

Across the River, on the northern bank, are the gleaming towers of Canary Wharf the financial center which rose from those abandoned docks in the 80s and 90s and to the left, with its discordant array of high-rise office blocks, the City of London.

Head west toward the unmistakable outline of Tower Bridge with its 19th century neo-Gothic towers, cross over a foot bridge to Shad Thames, once part of the largest warehouse complex in London, now converted into claustrophobic but sought-after apartments and a broad wharf lined with smart restaurants.

Keep following the app for a broader sense of pilgrim history. Borough Market, has existed for 1,000 years and is now a fashionable attraction with its stalls of fruit and veg, cheese and wine. Next, a replica of the Golden Hinde, the 16th century warship on which Francis Drake circumnavigated the world, 1577-80 and encouraged other explorers to set their sights on America. Along the riverbank the infamous Clink prison, where several Separatist leaders were imprisoned and hanged, is now a museum replete with gruesome exhibits.

Did the men negotiating to hire the Mayflower visit the Globe Theatre built in 1599 where Shakespeare’s plays were first performed? Probably not, but they might well have heard about The Tempest, which had its first opening there, thanks to Mayflower passenger Stephen Hopkins. He had led a mutiny against the skipper of a ship after it had been stranded on the Bermudas some 12 years before. Some say Shakespeare was much taken with the tale and based his play on the scandal. Hopkins might well have thought himself the inspiration for the wise Prospero but given that he was later fined for running a disorderly tavern, it is fair to say he was more like the bibulous butler Stephano.

Perhaps he reminded them of the words of Prospero’s daughter, the love struck Miranda:

How beauteous mankind is!

O brave new world,

That has such people in it!

Jones no doubt was mightily glad to leave the brave but daunting world of New England when he sailed home in April 1621 and relieved to be back in action that year carrying a less demanding ‘cargo’ than the settlers - a load of salt.

It may have been the ship’s last voyage.In 1624, the Mayflower was sold for the pittance of £128, eight shillings and precisely fourpence and was demolished or allowed to rot away.

This month’s Wicked insult: Flutch Calf-lollies

Flutch; The act of doing a million other things than what you are supposed to be doing - and slowly.

Calf-lolly; a fool, an idle simpleton.

Info: Mayflower 400. For guided tours; rbhistory.org.uk. The nearest stations are at Rotherhithe and Canada Water.

Stay: this is not really hotel country but the Double Tree Hilton in Rotherhithe Street was once the site of a 17th century warehouse.

Eat and drink: If you get that far, Borough Market is a treat.

Breaking out: The Thames Path is 184 miles long and stretches from the river’s source in Oxfordshire to the west, through the center of London to the Thames Barrier at Charlton, south east London.

Pictures: The Mayflower being demolished. The Angel.

The decision to drop the word Plantation from the re-creation of the Mayflower settlers’ first home was inevitable, given the justified furore over slavery, the role of colonial powers and their mistreatment of indigenous people.

Nonetheless, the danger is that history will be re-written and not re-interpreted.

The new name Plimouth / Patuxet is a label, Plimouth Plantation tells of a history which should not be ignored. To be logical, if the objection is to the word Plantation - with all its connotations - then surely there must be an objection to the place itself. If statues are pulled down are we saying the Plantation should suffer the same fate?

Here’s a piece written before this news broke. Read more:

Another clever headline from the New European for a piece on the reopening of several galleries in Normandy, France, in celebration of Impressionist artists. This is my favourite image - by Eugène Poittevin Read more

Bathing near Étretat

The fifth of a regular series of columns which appear in the Plymouth, Mass., paper , the Old Colony Memorial and across the region. It discusses the people, places and events that led to the Mayflower voyage from an English perspective. The author’s novel Voices of the Mayflower; the saints, strangers and sly knaves who changed the world is out now.

Last month we took a detour to the ‘faire and beautiful’ of Leiden, the Dutch city where the pilgrims lived for 12 years. This month another fork in the trail, takes us to Harwich, an out of the way port on the east coast of England.

Queen Elizabeth 1 described it as a ‘pretty place that wants for nothing’ and for centuries it was busily building ships and breeding sailors - though this year it is celebrated for one ship and one sailor. The ship; the Mayflower, which was hired in June, 1620. The sailor; skipper Christopher Jones, a Harwich man born and bred.

Some heirs to the Mayflower story are adamant that the ship was built in Harwich and announced as much on CBS News in 2013. Furthermore, they claimed the momentous voyage had actually started there and announced that they would raise £2.5 million ($3,087) to build a replica of the Mayflower and sail it proudly across the Atlantic.

Plymouth, Devon, they insisted, was only a bit player in the drama, which it is really, but that broadside launched the battle of the ports, as the newspapers dubbed it.

I visited the enthusiasts’ workshop some years ago when I was thinking about writing my book and admired the sturdy section of keel which had been assembled but I couldn’t help feeling their ambition was not matched by the harsh reality of time and resources. And so it proved. Instead of an ocean-going vessel an 18 foot compromise was bolted together and today is kept on a truck trailer ready to be towed to public events as an exhibit.

“Sadly, there is no proof that the ship was built here,” says local historian Richard Oxborrow. “We do know that Jones owned a ship called the Josian, which has built in Harwich, and that he swapped it for a share in the Mayflower. It’s hard to understand why because the Josian was probably bigger, better and newer.”

What is undeniable is that Harwich has a significant sea-faring past. Three ships from the port joined in the rout of the Spanish Armada in 1588, Harwich sailor Christopher Newport skippered a ship on the first voyage to Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607 and for centuries Harwich built ships for the Royal Navy until work dried up and it became something of a backwater.

Nonetheless the spirit of the port’s favorite son lingers. His house still stands in Kings Head Street opposite the Alma Inn, once a fine mansion, where his first wife, 17-year-old Sara Twit lived.

Sara died in 1603 and Jones remarried a few months later to wealthy widow Josian Gray, who had inherited her late husband’s house round the corner in Church Street. It was perhaps with her money that he was able to afford the 240 ton ship which he named after her and begin to trade with continental ports such as La Rochelle and Bordeaux.

Together they had eight children yet Jones still found the time to become quite a player in Harwich Society. By his mid-thirties in 1604 he was named as a burgess in a new town charter granted by King James and was responsible for administering the Poor Relief as well as acting as a tax assessor. His reputation was tarnished in 1605 when he was accused of keeping hunting dogs, which only ‘gentlemen’ with enough land were allowed to do.

In about 1611, he moved to Rotherhithe, a mile downstream on the Thames from the Tower of London and it was there that he was buried in 1622, one year after he returned from the voyage.

Even so, gentleman or not, Harwich hopes to make the most of his part in the saga. His home, which is privately owned, is to be opened to the public and turned into a small museum.

And though Harwich is not quite the ‘pretty place’ which delighted Queen Elizabeth much of the old town exists, with the five principal streets running in the medieval pattern from south to north to the water’s edge and intersected by alleys. As many as 37 houses are standing though their Tudor exteriors were covered in the Georgian era and the house were Elizabeth is reputed to stay in 1561 is now a car park.

A new museum on matters Mayflower is due to open in an old Victorian school and a commemorative walk talks the visitor past the key sights. The 19th century Halfpenny Pier - so called because the entry fee was just that, half a penny - is reminder of the days when Harwich was a magnet for day trippers, and the scores of red and yellow buoys stacked by the docks and the lightships bobbing in the water attest to Harwich’s role as a center for maintaining lighthouses and safety at sea.

A gantry which had been built for the pre-war ferries still looms rustily over the quayside. In its lee a small plaque commemorates the arrival of the first of many ships carrying thousands of Jewish children fleeing Nazi persecution in 1938/9. Two hundred of the children on the Kinderstransporte, as it became known, were housed in a nearby holiday camp.

One more stop; the council offices, a stern red brick Victorian building in which hangs the charter awarded the town in 1604 by James 1.

The two dense pages of Latin empowered Harwich to form ‘a corporate body consisting of a mayor and common council, comprising eight aldermen (from whom the mayor was to be chosen annually).’

The words might ring a bell. The charter shares many of the sentiments in the covenant drawn up by the men on the Mayflower such as the preservation of laws and ordinances. For corporate body, read ‘civil body politic’ and just as the mayor faced re-election annually, so too Plymouth’s first governor.

The covenant was later seized on by some as the inspiration for the US constitution so let’s enjoy the idea of an English seafarer having a hand in its composition. Why not? The men met in his cabin and as skipper Jones was in charge of everyone on the ship. Maybe he gave them the benefit of his knowledge.

“It’s a nice idea,” says Mr Oxborrow, unconvinced. “True or not, we’re proud of him in Harwich.”

This month’s Wicked insult: Ninny lobcock.

Ninny; a foolish and weak person, a booby, doofus, dingbat. Lobcock; a stupid blundering person. It also has a ruder definition which I will leave to the reader to work out.

Info: Mayflower 400 and Historic Harwich.

Stay: the Pier Hotel. On the quayside, good food, view over the boats bobbing in the harbour.

Eat and drink: visitors should try the old pubs which Jones might have visited such as the Swan in King's Head Street and the Globe, King's Quay Street. The Alma Inn and Dining Rooms has a sign boasting that it ‘has been at the centre of Harwich life since the 1850s serving ale to the citizens, sailors, soldiers and farmers of the wind that passed through.’

Break out: take a train from London’s Liverpool Street, which chugs along the wide sweep of the estuary with its mudflats and wading birds, spend time exploring, then take the Stena Lines ferry to Delfshaven and from there a quick train journey to Leiden.

Next: Following Mayflower along the coast.

Richard Holledge’s book Voices of the Mayflower is out now.

The Jones house

One of the most colourful characters in the great Mayflower adventure was Stephen Hopkins. Heres’ a piece from Hampshire Life; https://www.hampshire-life.co.uk/people/hampshire-locals-on-board-the-mayflower-1-6715120

The fourth of a regular series of columns from the other side of the Atlantic discussing the people, places and events that led to the Mayflower voyage from an English perspective. Today a detour across the North Sea to Holland and the ‘faire and beautiful city’ of Leiden. Home of the pilgrims from 1609 until 1620.

The first place to visit in Leiden is Stink Alley. A narrow gap between a soft furnishings shop and a silver maker it is lined with plastic refuse bins and bicycles. To call it nondescript is to give it a glamor it does not deserve.

It was here that William Brewster and his wife Mary lived and where the pilgrim elder and his young apprentice Edward Winslow published their radical pamphlets. Today it is better known as William Brewstersteeg (alley).

To reach this unprepossessing spot stroll along cobbled streets and by canals, past noble churches and fine gabled homes of warm red brick, and as you walk you will understand that of all the places on the Mayflower trail Leiden is the loveliest. In fact, it could be argued, the most significant because it was here that the pilgrims decided to sail to freedom.

What makes it all the more beguiling is that the pilgrims would recognize the place. Only look at the map to see how unchanged it is.

Of course, everything is in lockdown but the enterprising tourist board is refusing to abandon all their plans for Mayflower 400 and have set up a virtual program of talks, walks and museum visits to be broadcast on Saturday, May 16.

I’m lucky enough to have been on the Pilgrims Route with one of the guides, historian Marike Hoogduin, who brought the place alive for me, even in a howling gale.

Through the old cattle market we trudged, along the Galgewater where gallows stood and bodies swung, to the National Museum of Ethnology, (the Volkekunde), where its plan to explain the role of the Wampanoag in the Mayflower story will be told online. We stopped by an unimposing apartment block where a plaque announces that the artist Rembrandt was born in a house on that site. The story goes that the painter, who was born in 1606, used to play with the English children and might even have become friendly with a young Mary Chilton. Who knows? They were about the same age. It’s a nice story.

To lower the tone we paused in the old red light district and admired a pretty, pink dwelling which was once owned by a notorious prostitute nicknamed Groene Haasje (Little Green Hare). No wonder the God-fearing pilgrims were outraged by the ‘temptations’ of their new home.

Next, the Rapenburg, the most delightful of streets with its canal lined by elegant gable houses, and the site of the university where Brewster taught. Next door the Botanical Gardens where he might have acquired a book by herbalist Rembert Dodoens which he took with him to Plymouth. The pilgrims must have noticed the golden foliage of a laburnum tree planted in 1601 and maybe heard the story of the single tulip bulb which had been brought from Turkey in the early 16th century and became the progenitor of Holland’s tulip trade.

On the Rapenburg there is a beguiling cluster of bars such as the Grand Cafe Barrera - try the croquettes - and over the bridge, L’Esperance, a bruin cafe - brown café or pub - which opened to celebrate the defeat of Napoleon in 1814. A slogan on the wall reads; cold beer gives you warm blood.

Hard to disagree.

The God-fearing of the city, however, would have been drawn by duty and belief to the vast stony edifice of St Peter’s Church a few steps away. Inside, a small chapel in memory of the pilgrims and outside a plaque which poignantly lists the families who were buried there, including the community’s guiding light John Robinson who lived in a house opposite.

It was replaced in 1683, but behind the present building’s door is an unexpected delight - a courtyard of almshouses, one of 35 flower-filled squares tucked away in the city, all of them oases of calm.

Retrace our steps along the banks of the River Vliet and, in the lee of a bridge, we find a small statue, leaning forward, one hand reaching out, as if taking the first step to an unknown destination. It was hereabouts, that the pilgrims stepped on the boats which took them to Delfshaven and the Speedwell which transported them to the rendezvous with the Mayflower in Southampton.

The moment is vividly recorded by Adam Willaerts, a painter of the Dutch Golden Age, in Departure of the Pilgrim Fathers From Delfshaven. which was painted in the same year. It is striking how many of the passengers carry arms, even some women are holding pikes, and this apparently militant display has been used by some to promote the argument that the pilgrims were invaders, eager to conquer and kill.

I rather think it has more to do with defending themselves against the ‘wild lions’ they feared they would encounter.

The painting can be found in the Lakenhal Museum, built in 1640 as a hall for cloth merchants, along with classic depictions of the city in the 17th century. Curator Jori Zijlmans had plans to stage an exhibition which traced the story of the pilgrims from 1604 with paintings, documents and artefacts and is keen to frame their lives in the context of refugees and freedom today - something she will discuss online.

The camera will also go behind the door of the American Pilgrims House, a tiny museum given over to recreating life in the early 17th century. The creation of Jeremy Bangs, the pre-eminent historian on the Mayflower story, his work Strangers and Pilgrims, Travellers and Sojourners is the definitive account of life in Leiden in those years, and his museum one of the oldest houses in Holland. It is a dusty treasure trove of ancient books, chests, cooking implements and tools, all cluttered around a fireplace and a tiny bed. Apparently people slept sitting up. Who knew!

However, Leiden is not lost in the past. It’s lively where you want it to be - the cafes and restaurants are usually abuzz - but the streets are quiet. Cyclists, not cars, rule here.

Quirky too. More than 100 poems by such as Rimbaud, Pablo Neruda and Shakespeare have been inscribed on city walls but this, Travel Safely, by an Iranian poet Shafi'i Kadkani tells of a refugee fleeing his homeland and speaks to centuries of fugitives - and pilgrims.

It ends:

‘Travel safely then! But my friend, I beg you,

When you have passed safely from this brutal wasteland,

And reached blossoms, and the rain,

Greet them from me.’

For the pilgrims, the days of blossoms were a long way off.

This month’s Wicked insult: Jobbernol goosecap. Jobbernol is a misshapen head, a blockhead. Goosecap is a silly person especially a flighty young girl.

Info: virtual guide on Facebook and You Tube at 4pm European time, 10 am Eastern Time.

Contacts: Leiden Tourist Office (VVV Leiden), Stationsweg 26, 2312 AV Leiden, +31 71 516 6000. info@mayflower400tours.com.

To stay: Hotel Steenhof Suites, a converted house with handsome stepped gables, rooms with beams and original fireplaces. Spectacular breakfast of eggs cocotte, nutty yoghurt, cold meat, cheese and croissants.

To eat: The Waag, a cavernous brasserie, once the old weigh station on the site where the pilgrims landed after leaving Amsterdam. More sophisticated, the Sabor on St Peter’s Square. Best in summer when you can sit outdoors.

Along the Galgewater - then and now

Leiden in the pilgrims’ day