This piece about another well focused show at the Watts did not make it to the New European web site. So here it is. An appropriate piece for the days we are in.

Barriers were erected. Police called in to contain the crowds as they jostled and pushed to get a closer view. The object of their fascination - and their disgust - a painting.

One critic dammed it as ‘too revolting for an art which should seek to please, refine and elevate.’ Another believed that it would persuade ‘the philanthropic and true-hearted to endeavour to combat this misery which is in our midst.’

The melee took place at the Royal Academy in 1874. The painting was Applicants for Admission to a Casual Ward by Sir Luke Fildes and it is one of an exhibition Art & Action: Making Change in Victorian Britain at the Watts Gallery which examines how artists of the day used their work to expose poverty and bring social justice to a country deeply divided by class and money.

The gallery was founded by the eminent Victorian artist G.F.Watts (1817-1904) and his wife Mary (1849 - 1938) and is set in the village of Compton near Guildford, Surrey, where the couple took positive action by establishing pottery classes for 70 less privileged local villagers and providing employment in the Compton Potters' Arts Guild which lasted until 1956.

After World War One had shut down most of London, Mary wrote: “We may remember this little gallery... was here open to the public when the great art galleries in London had to be closed.”

Sadly Covid-19 is no respecter of even the bucolic fastness of the Surrey countryside and the gallery is closed - though still planning to re-open and continue with the show until at least March 21. In a reminder of the uncomfortable way history repeats itself two small images in the show underline how pandemics are nothing new and how cholera killed millions worldwide until the discovery in the 1850s that the disease was not carried by air but by water.

In Death’s Dispensary (1866), the skeletal figure of death lingers by a contaminated pump, deadly enough to infect hundreds of people in an entire neighbourhood, while W. A. Atkinson (c.1849-1870) celebrated the opening of the first safe water pump in Holborn, London, in 1859 with The First Public Drinking Fountain (1860).

Atkinson was eager to send a message to the public about the importance of clean water and changed his first sketch to show how middle class people, not just the poor and ignorant, should also drink from the fountain by altering the dress of the mother and daughter and painting them in clothing commonly associated with the upper middle classes. In doing so, he suggested, that curbing the pandemic requires all London residents to put health and hygiene above class differences.

Something of a familiar refrain 160 years later. ‘We’re all in it together,’ exhorted Chancellor Rishi Sunak for fear we all drove to Barnard Castle to have our eyes tested and despite the fact that poorer areas have double the death rate from COVID-19 than wealthier.

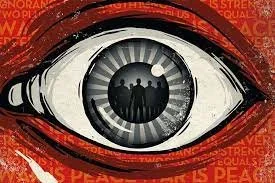

It was in 1839 that the first stirrings of a national social conscience were articulated by philosopher Thomas Carlyle in his book Chartism in which he raised the Condition of England Question. He exposed a society riven with inequality by the industrial revolution as it powered its remorseless way bringing wealth to many but famine, unemployment, pollution and extreme poverty to many more.

He hoped to persuade his readers to repair social divisions, albeit from the perspective of - and for - the benefit of white ‘Anglo-Saxon’ Britons and felt no contradiction in the way he promoted his concern for the poor with anti-Semitic and pro-slavery views. Nonetheless his work on inequality had a significant influence on Victorian artists such as William Morris and G F Watts himself, as well as writers Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Charlotte Brontë and Elizabeth Gaskell.

There were few statistics to support his revelations of what became known as the ‘Hungry Forties’ whereas today the stats are overwhelming and the parallels depressing. For example, the independent Social Metrics Commission found that in 2017/18 about 14.3 million people were in poverty in the UK, while the Office for National Statistics reported in September that redundancies had risen to a record 314,000.

Embarrassingly, Unicef, the UN agency responsible for providing aid to children worldwide, offered a grant of £25,000 to help supply18,000 breakfasts for school children in Southwark, South London.

These are issues which tend to be ignored by contemporary artists who concentrate on the failings of democracy, race and gender identity rather than, say, highlight the plight of the homeless who lined up in Trafalgar Square last summer (2020) to collect free meals. Not much of a step back from there to Fildes’s Applicants for Admission to a Casual Ward which depicts with distressing detail the shivering, starving, outcasts, queuing in the snow to qualify for a ticket for a one night stay in a workhouse.

Charles Dickens, after seeing a similar group outside a work house in Whitechapel, East London, described them as: “Dumb, wet, silent horrors! Sphinxes set up against that dead wall.”

Perhaps an even bigger impact on the national consciousness came with the publication in 1842 of a parliamentary report, The Condition and Treatment of the Children employed in the Mines and Colliers of the United Kingdom.

Widely available in bookshops, it detailed the terrible conditions experienced by men, women, and children in mines with - for the first time in a public enquiry - gruelling images of women and children scrabbling through tunnels of coal on hands and knees, crouching to pull heavy carts, lying on their backs to hack at the coal surface. Almost more shocking to Victorian sensibilities than the plight of the miners was the revelation that women and men were partially clothed when working together.

Such was the outcry that the Government brought in labour laws which prohibited all women from working in the mines and limited employment to boys over the age of 10.

Much of the report’s impact was down to the illustrations, a device used by a revolutionary new magazine, The Graphic, which was launched in 1869 and employed many of the prominent artists and writers of the day such as Fildes and Sir Hubert von Herkomer (1849-1914). His engraving Old Age: A Study at the Westminster Union (1877) portrays a group of elderly women gathered in a dismal workhouse, dressed in drab regulation uniforms, sewing. Perhaps he felt the image was too bleak, for in a later painting entitled Eventide he added a posy of flowers to the table and brought a touch of animation to the faces of the old women which suggested perhaps that their situation was not so miserable - or perhaps that he did not wish to upset his viewers with an unpalatable truth.

There was an ambivalence about the way the subject of poverty was treated. In a four volume report by journalist Henry Mayhew (1812-1887), London Labour and London Poor published in 1851, he interviewed the city’s street folk - the rat catchers, a rape victim, vagrants and street sellers - and questioned who deserved charity by categorising his interviewees as ‘those that will work, those that cannot work, and those that will not work,’ suggesting that some people ‘deserved’ help, while others did not. In other words, the ‘deserving poor’ so often touted by modern governments as they embrace austerity and reduce financial support for those who do not appear to have done enough to warrant assistance.

The people he wrote about objected so much to this stereotype that they founded the Street Trader’s Protection Association to defend themselves against his claims.

Journalist William Blanchard Jerrold (1826-1884) teamed up with French artist Gustave Doré (1832-1883) to produce London; a pilgrimage in 1869 with 180 engravings which was intended to document those class differences which existed in the ‘shadows and the sunlight’ of the city.

They hoped to influence their affluent readers to form ‘a higher estimate of the hand-to-mouth population’ with images such as a squalid back to back housing in the lea of a railway bridge with a train belching smoke, beggars and street performers and crowds queuing for a steam boat trip on the Thames.

Contemporary critics accused Doré of ‘inventing rather than copying’ while another claimed that, ‘Doré gives us sketches in which the commonest, the vulgarest external features are set down.’

Unsurprisingly Victorian writer John Ruskin deemed that many of the paintings displayed at the Royal Academy at that time were like scenes from an illustrated newspaper - a judgement which could not be made about the works of G.F. Watts himself who Ruskin declared was ‘the only real painter of history or thought we have in England.’

Despite making his reputation as a portraitist and painter of monumental scenes of myth and history, Watts was profoundly influenced by the exposés of poverty of the 1840s and, as befits the founder of the gallery, three of his paintings dominate the exhibition.

The Song of the Shirt (1847) is a melancholy portrayal inspired by an investigation into the conditions of factories and trades which revealed the exploitation of seamstresses, who worked for up to three days without rest and received only a pauper’s wage. The exhausted woman is seated in a desolate room, she covers her face in her hands, her task is unfinished. The candle on her table has burnt out. She is resigned, defeated.

Perhaps the most haunting is Found Drowned (1848-50). A woman is lying by the Thames, half in water, under Waterloo Bridge. She has drowned herself, her arms stretched in a cross as though crucified. A chain and a heart-shaped grasped in her hand suggest she has been betrayed or abandoned by a lover.

A preparatory sketch of Under a Dry Arch (1847) shows that Watts originally intended to portray a young, homeless mother surrounded by her children but in the final picture, the female figure shelters alone, hunched against the cold, lost in the shadows of the arch of Blackfriars Bridge in London. Mary Watts said that the woman was dying... ‘with all the anguish of a long life scored upon her face.’

Her husband summed up the poignancy and power of the painting. “It had no beauty,” he declared. “But it has a purpose. It, I hope, arouses pity for human refuse.”

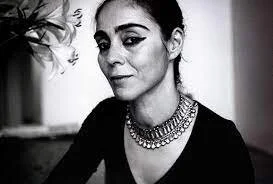

Art & Action: Making Change in Victorian Britain at the Watts Gallery, dates to be announced. Artist Chila Burman will give an online interview. Artist talks, courses, family and education events, will be hosted from the home and studios of G F and Mary Watts.