Deep in the mining region of Brazil’s Minas Gerais, the heart of the old gold mines, is a man-made tropical jungle replete with galleries and works of art. And a snake.

Dancing in the ruins of Gaza

A moving exhibition at the small P21 gallery in London avoided direct political messages, did not show the worst of the destruction and despair. But did produce images as works of art, and as images of resilience and some hope.

Read more: https://www.thenewworld.co.uk/richard-holledge-dance-against-oblivion/

Fishy business? Or idealists with a cause?

Splendid read about the young men and women who thought they had found the answer to the world’s ills in Soviet Russia and fought fascism with art

Water, water everywhere. Except when it's not

A small, thoughtful exhibition at the Wellcome Gallery looks at the history of water use and misuse and has salutary warnings about what might come next - will come next - if the world doesn’t react.

No studio shots, no flashes, no unnatural poses. Chile. Always Chile

The photographs of Paz Erraruziz are a painful reminder that fascists from left or right have no truck with individual liberties. She braved the terror of Augusto Pinochet’s regime to record images of the dispossessed, the lonely and the disenfranchised

Read more: https://www.thenewworld.co.uk/richard-holledge-eyes-from-the-shadows/

What price reality? It's a fake, fake world

Photographer Zed Nelson exposes the commodification of nature in this, his latest collection. He exposes a world in which nothing is quite what it seems. Actually, not at all what it seems.

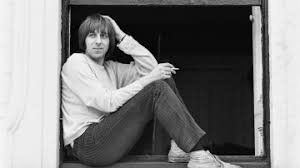

Rage, rage at the telling of a bad joke

I met the late Barry Fantoni a few years ago. Splendidly his own man

Private Eye’s Barry Fantoni is in magnanimous mood. “Cartoonists in this country are very good,” he says. “They are as good as they get.”

But then, in a seamless volte face worthy of Eye heroine Glenda Slagg herself, he goes off: “Martin Rowson is rubbish; Peter Brookes? Rubbish; Nick Garland; he’s rubbish - the only joke he’s got is that ‘with apologies to....’ formula.”

So that’s the cartoonists for The Guardian, The Times and The Daily Telegraph dispensed with.

Donthca just love him. Fantoni joined Private Eye in 1963, almost at the birth of the magazine and the satire era. His cartoon the spiky Scenes You Seldom See still decorates the letters page and as EJ Thribb he pens Poetry Corner, the unpoetic tribute to the departed which starts ‘So. Farewell Then....’

“I don’t feel comfortable unless I am having a rage at something,” he says. “I still write letters to newspapers. I just can’t stop.”

Now he is putting himself up for scrutiny - maybe even a rubbishing - by holding a show of his cartoons as well as his landscapes and portraits.

“The show is a reaction to the fact that my mum died last year. She paid for me to go to Camberwell Art College when I was 14 so I thought I would put on an exhibition to celebrate what would have been her 100th birthday.”

Fantoni produced a pocket cartoon for The Times during the Eighties and another for the now-defunct The Listener for 21 years.

“It all started for me when I held an exhibition on New Year’s Eve, 1962,” says the 69-year-old. “The art critic of the Daily Express came for a drink and a story. He had seen in the catalogue a picture of the Duke of Edinburgh in his underwear surrounded by cut out outfits such as a boy scout’s uniform and a kilt.

“These days it wouldn’t raise an eyebrow but by lunch time it was on the front page of the Evening Standard. Shock! What have they done to the Duke of Edinburgh?

“Richard Ingrams, who was editor of Private Eye, saw it and asked me to work there and it’s been virtually the same four or five of us who were there at the start who do the pages of jokes in the middle.

“Private Eye seems to be at its strongest when it attacks the way the media reports stories rather than attacking the institutions themselves. What I find obscene is that the writing is so obviously bogus.

“Most papers are like a weather vane. They don’t have a view, just register where the wind is blowing. Columnists are like Glenda Slagg, incapable of understanding anything much more than PR handouts. They are being paid to write even though they have no opinions at all.”

Do any cartoonists make the grade?

“I think Vicky of The Mirror in the Fifties and Sixties got it right all the time and so did David Low of the Standard. They could draw properly.

“Look at the Osbert Lancaster’s cartoons - they are still relevant, they could have been drawn yesterday. Look at the work of Leslie Illingworth who was at his best in his Punch days. He produced full pages of political comment which, artistically, were as good as it gets. Beautiful.

“The two funniest cartoonists of my generation were Bill Tidy, who did The Cloggies and Larry, who studied painting and drawing and knew you had to make people look funny in cartoons. I like John Husband’s work and I think Michael Heath is exceptionally good. He is observant, he is current and you know exactly who you are looking at when you look at one of his figures.”

But just in case it sounds as if he’s mellowing in his old age he even has a swipe at Private Eye itself.

“The cartoons are funny but I don’t think the drawings are very good. Some are just like hand writing aren’t they? I think you could draw better than that.”

Barry Fantoni: Public Eye, Private Eye Thomas Williams, Old Bond Street 22 April – 22 May 2009

Photos from the front line. They might surprise you

This is a piece I wrote for the New European. The work of these young Ukrainian photographers is mightily impressive.

There is little to lift Ukrainian photographer Rehina Bukvuch from her mood of bleak pessimism.

“We believe Russia is preparing for another offensive. There is no sense of a ceasefire, on the contrary Russia is bombing us more than ever. We are anxious about Trump and his policies but in reality we have no other choice.

“So for us, if the Russia comes all of this will end. We will either have to leave our country or be sent to a gulag - there will be no life for us. We know Russia’s policies and if they occupy us they will try to completely erase us so that Ukraine never resists again.”

The ‘all’ she refers to is, counter-intuitively, an art scene ‘thriving like never before’ with new galleries and exhibition openings as well as a growing focus on Ukrainian authors.

It is a scene she has contributed to as part of an imaginative scheme to inspire artists who have been compelled to swap camera or paintbrush for guns and drones by connecting them with artists who can work in safety far from the conflict.

The driving force behind the project, cultural activist Alona Karavai, says: “We wondered how we could help artists who were on the front. We thought, okay, we can help keep alive their sensibility by connecting them using emails, drawings, letters and photographs and encouraging them to work in tandem to create works, however small, however simple.

“The important thing is that the voice of the artists on the front line can still be heard.”

Rehina Bukvuch compiled a photo album for artist-turned-soldier Yevhen Korshunov, a friend from the youthful art scene they shared in Kyiv before the war

When he returns from the action, he will find the album - only three inches by 1.5 - filled with pictures of old friends and warm messages such as ‘Zhenya, warm hugs and a little kiss for you’ sealed with an extravagant smacker. He will be reminded of his peripatetic life on the front line where he is being moved from billet to shabby billet by quirky photographs which he took himself and sent to Bukvuch.

The album speaks of loneliness and dislocation, but it is a reminder of a time neither will forget and a small but eloquent gesture of defiance against the ever present threat of defeat and destruction.

The results of these ‘tandem’ works have been shown in an exhibition at an art centre, Asortymentna Kimnata in the small town of Ivano-Frankivsk, deep in the Carpathian mountains about 350 miles west of Kyiv. The place is also temporary home to 40 IDPs (Internally Displaced Persons) who have the opportunity to join other artists in a fever of creativity, including a display of deceptively colourful paintings by women, most of them amateurs. Deceptive because they are all grieving someone lost in the war.

The album is one of the more low key contributions to the show which is called Do Toads Sing in the Walls? after an artist wrote a song about toads which had settled in the buildings where his unit was stationed. Others are more disturbing.

While recovering from a wound in hospital, Klementyna Kvindt, a drone operator, poet, and ornithologist, complemented her recordings of birdsong with documents, photos, and poems which were collated in a book made of zinc by Olha Babak. Words set against stormy landscapes, or simply on the grey of the metal create a mood which is both eerie and forbidding.

The poems of Yulia Bondar are cries of anguish delivered in a monotone: I bury spring in the black soil / of my barren heart / How many springs lie buried / in this black land? and her words are matched with animated drawings by Mashyka Vyshedska. Hands reach up to bring succour to a woman, only to fade away, flowers briefly bloom and die. A serpent curls around a female torso, leaving behind bloody scars.

The very fact that the works have overcome the constraints of geography and the challenges of communication is in itself a triumph, yet as Karavai, herself an IDP having been forced to flee Donetsk in 2014 when the Russians invaded, acknowledges this kind of grass roots activity will be targeted by the enemy.

“Putin wants to destroy our traditions, our free cultural expression,” she says, but insists that the venture is not merely about promoting national pride.

“It is not about nationalism,” she says. “But more about preserving a culture which is free and democratic. For me, art is a way of existence, of people being together, being fair to each other, and this for me, in a way, is the civilisation which Ukraine is fighting for against Russia. It's not about the Ukrainian nation against the Russian nation, but about one way of living, and art for me, is a part of this way of living. The civilisation we are protecting, is outside the notion of nation.”

That explains why the contributions are more reflective than the ugly images of death and destruction which are horribly routine in newspapers, social media and TV.

It’s a shift recognised by Kateryna Radchenko, curator of the Odesa Photo Days festival, who says: “On February 24, 2022 - literally overnight - every photographer, visual artist, and ordinary citizen with a camera became a documentarian of the war, often without training or proper gear.

“They became witnesses, transforming their cameras into tools to collect evidence of this unjust war, the destruction of cities, architectural heritage, and infrastructure; the bodies of killed civilians; torture and interrogation chambers. They took massive numbers of selfies, firstly to share with their families to show that they were alive and but also to prove to themselves that they were still alive. This focus is a kind of self protection.

“Now it has changed because we have had three years of adaptation, three years of living under the attacks, and artists stopped being afraid and hiding in shelters and started to think more and reflect more by using associations or symbols to describe their feelings and their thoughts rather than direct images.”

Testimony to that change can be seen with the results of a mentoring programme for young people she has helped establish.

“Thousands of kids suffered from the occupation in Mariupol, in Kherson and the attacks on Kharkiv,” she says. “We decided to help them use photography to work through this traumatic experience and also to provide them with the skills to earn money as photographers.”

One of those is Ivan Samoilov who has lived all his 20 years in Kharkiv. After the 2022 invasion he spent two months taking pictures of his hometown. ‘Only rescuers, old people, volunteers and homeless animals maintained some kind of life in the ruined city,’ he says.

His photographs include a lad flexing his muscles on a playground apparatus framed by the ruins of a block of flats behind him, in another, the eye is drawn to a bold flower bed of marigolds before taking in the devastated building behind. Two men on a pedestrian crossing a deserted street, the golden spires of a church catch the sun. As with all the images, the ruined buildings seem almost incidental. Life, after a fashion, goes on.

An essay on volunteers by Artem Baidala, 21, from Dnipro, shows a man concentrating fiercely as he crunches through the rubble carrying materials for construction work on homes hit by missiles, a dachshund trots along before him. Young men take a break with a game of football in a yard. It all looks so normal.

Odesa, with its beaches and noble architecture, has been ravaged by Russian missiles. Tim Melnikov, a 19-year-old student, chronicled the effects of the war on the city with its taped off beaches and piles of sandbags which is now ‘deserted and gloomy, but not broken.’

Radchenko has witnessed a growth in conceptual work, cleverly expressed by Olia Koval, 21, in Memory. A shabby room, sparely furnished with a table, a chair, pictures on the wall, clothes hanging from hooks is transformed in eight frames from rich dark shades to one in which the colour is almost entirely bleached out.

‘Time seems to have sped up after 24 February,’ she writes. ‘Large amounts of information carry you away from where you are. It’s hard to remember what exactly surrounded you.’

And few contributions are as conceptually dauntless as that of Sofia Konovalova, 19, from Kharkiv, who poses nude in a cupboard with a suitcase. In The Place where I Live she captures the oppression that has afflicted her since the invasion. Nevertheless in that claustrophobic confine, life goes on, cleaning teeth, brushing hair, reading a book perched on the suitcase which is packed and waiting to return home, just like her.

Whether it’s a workaday selfie or the ambitious dialogues between artists hundreds of miles apart, the creativity of Ukraine’s young artists is undiminished despite Radchenko’s belief that the world is ‘bored with Ukraine’ - a pessimism she has felt long before Trump and his cohorts abused the ‘dictator’ Zelensky in the White House.

To stir the world from that boredom she has organised a project with Magnum Photos, Beyond the Silence, presented the endeavours of an international array of talent in Lviv.

“The show will help to prove that we are still alive and that we are a different country with a different identity, with our own culture and our own voice, which we want to share, and to make it, like, really loud.”

“On or about December, 1910, human character changed.” Virginia Woolf

It’s always a joy to find an exhibition as far removed from the blockbuster or the overwhelmingly impersonal galleries, think Prado, Louvre, Tate Modern, as this in the wonderful Charleston Museum.

All good ideas arrive by chance.

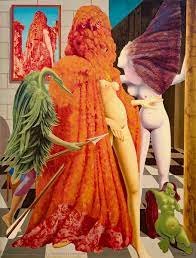

Trying to get inside the mind of Max Ernst, the artist who enforced his own madness on the world. A marvellous exhibition at the Circulo de Bellas-Artes in Madrid. Great bar as well!

Read more: https://www.theneweuropean.co.uk/richard-holledge-max-ernsts-marvellous-madness/

Cash in on the bank that thinks it’s an art gallery. Two versions of the same story here. Money makes the (art) world go round

Read more:

https://www.theneweuropean.co.uk/richard-holledge-the-bank-that-thinks-its-a-gallery/

Good publicity and generous philanthropy. Huge profits. Nothing new about that as a business model for an ambitious bank.

The Medicis, the powerful Florentine banking dynasty of the 15th century, understood that all too well, spending some of their vast fortune endowing churches and cathedrals and sponsoring artists such as Donatello, Botticelli and Michelangelo to atone for their particular brand of usury and corruption.

It is a philosophy embraced by many contemporary banks, perhaps few more than another Italian

banking titan, Intesa Sanpaolo - not the usury and corruption, of course - which has won welcome publicity for its philanthropic role as lead sponsor of the ravishing Siena: The Rise of Painting now at London’s National Gallery.

The corporate world loves art. Banks buy paintings to adorn their boardrooms and impress their clients with a Picasso here, a Warhol there. No self respecting foyer is complete without a Tracey Emin to welcome a would-be investor.

How reassuring it must be for the shareholders to know UBS owns more than 40,000 art works or that Deutsche Bank’s London HQ is embellished with works by Damien Hurst and Anish Kapoor. Good to know Barclays Bank owns one of the most valuable collections of them all with their offices bedecked by David Hockney, Bridget Riley, Eduardo Paolozzi and many more.

These collections are crucial marketing tools when it comes to promoting an image of wealth and shrewd judgement. And, of course, they scream - in a subtle sort of way - money, money, money.

As JP Morgan Chase (35,000 acquisitions) explains on its private banking site: ‘Art transcends economic environments, providing cultural enrichment and a broadening of your asset classes.’

From Preach by Carrie-Anne Weems

Intesa Sanpaolo wouldn’t disagree with that but their business plan has at least one material difference; they are a bank which thinks it’s an art gallery - or rather four galleries. One of Italy’s biggest banks, it has cultural outposts in Milan, Naples, Vicenza and Turin and itself owns 35,000 artworks. Unlike its global rivals, where most of the works stay hidden from view, it owns permanent collections which are open to the public, schoolchildren are encouraged to come, look and learn, students enjoy free entry up to the age of 18 and courses are available for graduates to learn how to curate an exhibition or manage a gallery.

The other fundamental difference is that though there is a programme of contemporary work, the collections have been decades in the making and are inspired by the art and heritage of the region.They are not just a splashy gesture on an office wall.

Perhaps the one man most responsible for this was Milan banker Raffaele Mattioli who was managing director of Banca Commerciale Italiana between 1936 and 1972. Known as ‘the humanist banker’ he was driven as much by his commercial instincts as his passion for art which he displayed in the bank’s elegant offices on the Piazza della Scala.

He died long before his bank was subsumed in 1999 into Intesa Sanpaolo but, happily, the takeover has stayed true to his ethos by transforming the old bank from a building of business into a building of culture, the Gallerie d’Italia.

Its fascinating collection ranges from plaster works by Canova to paintings celebrating the Risorgimento, Italy’s long struggle for national unity, by way of genre representations of the working class and landscapes of Lombardy region. The artists lack the reputation, or the commercial dazzle of Hirst and Co, but the work has an authentic charm which speaks to the culture of the region and emphasises Milan’s significant role in Italian culture during the 1800s.

Canova in Milan

More recent art from the 50s and 60s is not neglected with a selection - again from the region - including Umberto Boccioni, Lucio Fontana and Alberto Burri and this June it hits the Sixties with Beatles in Milan, (June 25– September 7) displaying photographs of the lads posing in front of the Duomo and twisting and shouting on stage.

The photos are taken from seven million photographs from the 1930s to the 1990s which were acquired from an Italian photo agency and stored in the Turin gallery, a palazzo rebuilt after World War Two.

It’s a marvel of ingenuity using wood panelling, stucco work, gilt mirrors, furniture and tapestries, taken from nearby palaces which had been reduced to rubble but it’s fair to say the centre of attention is the new underground space which is given over to photography.

Next up is Italian Olivo Barbieri. Other Spaces (until September 7) with dramatic ‘helicopter’ shots of Chinese city life followed in April with a retrospective of Carrie Mae Weems. The Heart of Matter which includes Preach, a project exploring the role of religion and spirituality among Americans of African descent.

St Ursula

The gallery in Naples has permanent collection of 500 vases crafted between the 5th and 3rd centuries BC and an array of paintings from the 17th century to the early 20th. How surprised the experts were to discover after the local bank had been taken over by Intesa SanPaolo that a painting which had hung unremarked in the boardroom was none other than Caravaggio’s The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula which was shown at London’s National Gallery last year (2024).

By way of contrast, the current show stars Andy Warhol: Triple Elvis.(until May 4) with the silk screen paintings of Marilyn Monroe, Mao Tse-Tung, and the disquieting Electric Chair together with gun-toting Elvis Presley in silver and black based on a scene from the 1963 film Flaming Star.

Underpinning all these enterprises is the bank’s Progetto Cultura, a scheme to promote the bank’s commitment to the arts and to the philanthropic schemes which accompany it.

“Our history is the living part of our being, of our brand,” says Michele Coppola, Director of Art, Culture and Historical Heritage. “ Now we are contemporary philanthropists, supporting art and culture.”

As he intimated it would be naive to think this is not part of a brand building enterprise. After all, this is a bank. It’s aim is to make money. In December 2023 Intesa Saopaolo announced assets of €963,570 million (£802,305m) and in an unusual move put a price on its collection of €850 million (£707,822).

Nonetheless, there’s a real sense of genuine altruism about one scheme, La Restituzioni, which was launched in Vicenza in 1982 and has enabled the restoration of hundreds of paintings and sculptures which had lain discarded in churches, council chambers and cultural institutions. The results will be on show in Rome in the autumn.

Coppola says: “Restituzione is part of our roots, of our history, of our DNA. It shows how have a responsibility to our heritage and proves we are on the side of public culture by investing in the community we are a part of.

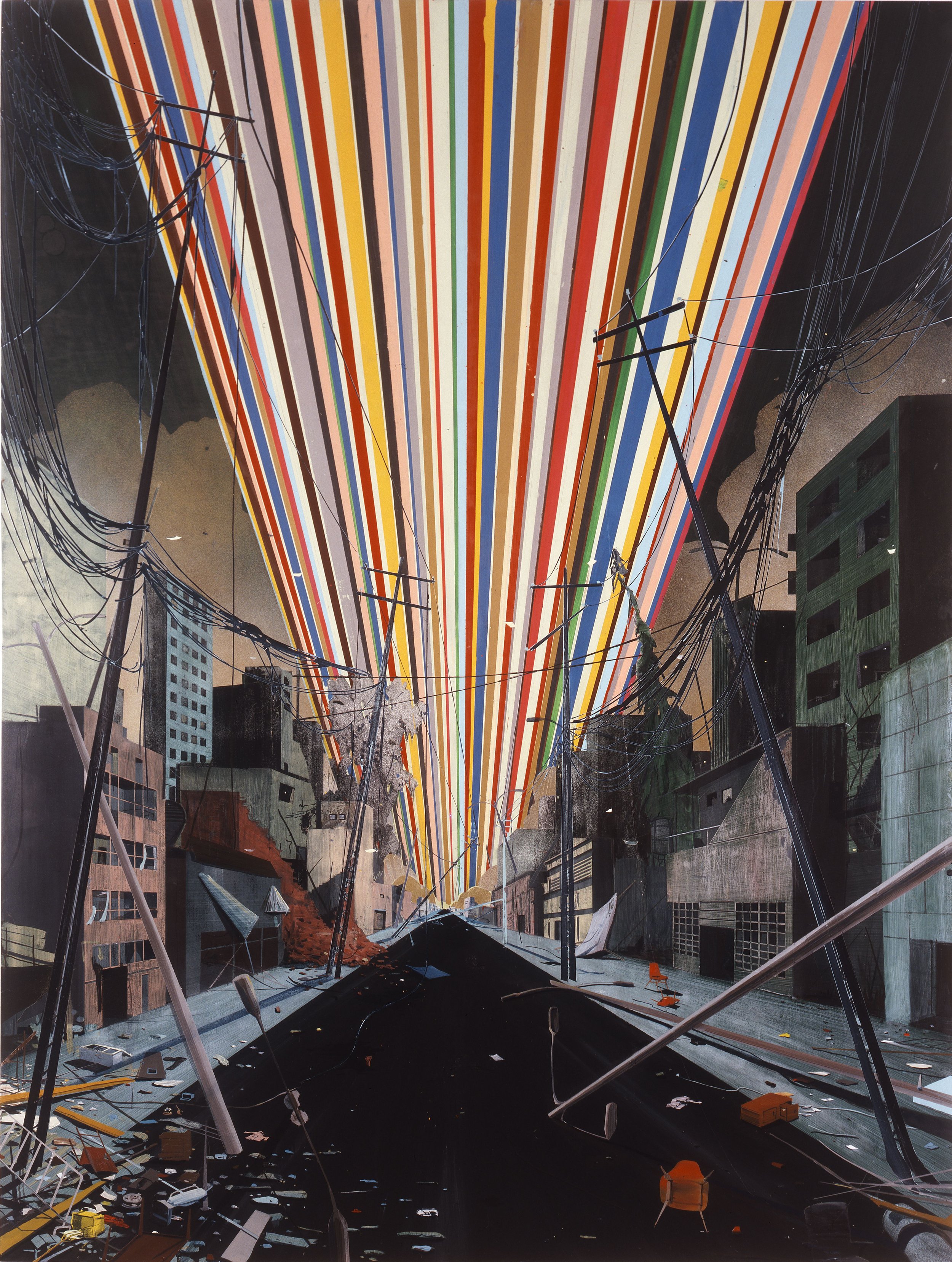

Apocalypse then... and now

We’re all doomed. Or are we? An intriguing exhibition in Reggio Emilia, Italy has the answers. Well, at least some dramatically visual suggestions.

The Book of Genesis 7; 4. God’s message to Noah: ‘I will cause it to rain upon the earth forty days and forty nights; and every living substance that I have made will I destroy from off the face of the earth.’

It’s tempting to see world on the brink of divine destruction as the inspiration behind an exhibition at the Collezione Maramotti, Reggio Emilia, Italy, (until Feb 16) not least because it is titled Through the Floods but also because the first image to greet the visitor is that of Noah’s ark.

But the show’s themes which are listed as ‘natural disasters; human abuse of animals and nature; man’s violence to man and the horrors of war; illness and death’ are not restricted to religious iconography, however potent.

The litany of catastrophe which has afflicted the world for centuries is reflected by the gallery’s choice of works which date from a second to third century stele of a woman’s head in the style of Ancient Egyptian funerary monuments, through melodramatic representations of violence and disaster from the 16th and 17th centuries and on to shifts of style and emphasis in the 21st century works, many taken from the last 10 years.

As curator Sara Piccinini explains: “There is something apocalyptic about the way we are immersed in a terrible flux, from floods and typhoons, to war and famine. There may be something Biblical about what is happening to the world but we are attempting to reflect the way the news is accelerating in intensity and for that we need to show contemporary work.”

That might explain why an early working titles for the exhibition was Apocalypse Wow! Conceived during the pandemic, planned during years of unprecedented global tragedies such as typhoons in Taiwan, floods in the Sahel Region of North Africa and the hurricanes which hit the USA, the show opened, with horrible irony, the week the first floods tore though Valencia killing hundreds.

While the show does open with After the Deluge (1864) by 19th century Italian painter Filippo Palizzisets, a traditional representation of the Noah story with the Ark atop Mount Ararat and the liberated animals happily gallivanting around, a salutary note is struck by a radical version of the legend in Spoiler Alert (Extreme Weather) (2018 - 2019) by American Andy Cross .

Inspired by Jacopo Bassano’s The Animals Entering Noah’s Ark painted in 1570, he shows how mankind has failed to deal with climate change and led by Noah, in this case a Rastafarian farmer, the animals are to be deported in a 21st century ark, a multi-mirrored space age dome, to a planet where the inhabitants have accepted their responsibility to protect the world.

Given the show’s title, inundations and ‘weather events’ are a recurring theme. A house, in a painting from 1837, is swept along like some domestic ark by Alpine torrents, sailors flee from a storm-torn ship only to drown in the turbulent waters. In the deceptively simple Irene 2011 by Monica Bonvicini, a wooden house, typical of the hundreds wrecked by that storm and many others such as Katrina and Helene, has been torn apart by the deluge. In stark black and white it is an understated image, but one which speaks of greater tragedies.

Back to the Bible: ‘God said unto Noah, The end of all flesh is come before me; for the earth is filled with violence through them... and, behold, I will destroy them with the earth.’

The gallery may well be reluctant to embrace such religiosity but certainly goes for Apocalypse Wow.

A graphic 19th print of The Plague in Florence, inspired by Boccaccio’s La Decameron, is a nightmare of prostrate bodies pleading for salvation from the Almighty. A scene of despair and death overseen by a priest before a banner decorated with a skull and cross bones. He is holding a flaming brand - in part to protect himself from the disease but also to keep the mob coming closer.

The fratricidal onslaught by the Cain on his brother Abel is brought to life in Domenico Piola’s 17th century Cain and Abel in a swirl of movement and colour. Cain, jealous that God had accepted Abel’s offering rather than his own, beats his brother to death with the jawbone of an ass. Looking on, a lamb, which signals the decline of human morality.

The inclusion of Fellice Boselli’s Macelleria (1720) seems an odd choice, after all it’s only a butcher’s and of no offence unless you are vegetarian. But the sheer bloodiness of it, the carcasses, the staring lifeless eyes of the dead beasts is so brutal, so ugly, that you can almost smell the dead meat. It wreaks of violence.

And then there’s the horror of war. In Metanarrativas No. 1 (2024) the Cuban Ariel Cabrera Montejo has a young soldier wearing virtual reality goggles to observe a military massacre in which bodies have been strewn across a battleground. The painting drew inspiration from the 1898 war between the United States and Spain that ended in an American victory and Cuban independence, but it could be today. It could be Gaza, Ukraine or Sudan.

Photojournalist Ivor Prickett kept his camera trained on a woman in Mosul Old City, Iraq, at the height of the conflict in 2014. She sits on a plastic chair, waiting and watching as an excavator digs through the ruins of her home, sending swirls of dust over her, dumping mounds of stone and wreckage beside her.

Underneath the rubble, the bodies of her sister and niece who were killed by an airstrike. She did not move until the bodies were eventually found.

“Her defiance was one of the most heart-breaking and inspiring things I have ever seen,” says Prickett. “It seemed to speak volumes about the futility of war but it was also a testament to the strength people have in this fractured region.”

If she was phlegmatic in the face of tragedy, Käthe Kollwitz’s etching from 1903, Mother with Dead Child, is a primal scream of loss. Kollwitz sketched herself naked in front of a mirror holding her seven-year-old son Peter who was to die in 1914. Her aim was to dramatise the high rate of child deaths in her home city of Berlin where many did not live beyond the age of five.

With such imagery this is an exhibition shrouded in pessimism despite the gallery’s insistence that there is some scope for optimism - or at least to take an equivocal view of the future.

This ambivalence is best expressed by Jules de Balincourt’s startling Blind Faith and Tunnel Vision (2005). Set in a darkened room to heighten the dramatic effect, it depicts a wrecked street; buildings lurch, telegraph poles teeter, the chaos of destruction is accentuated by scattered chairs, debris and shards of timber. Has the destruction been wrought by the irresistible force of a storm or by human violence, a bomb attack perhaps?To add to the ambiguity a rainbow of stripes, beautiful but threatening, soars away into space.

Does it portend the end of the world or a bright new future poised to emerge from the ruins?

Those who take the darker view will find little comfort In Joan Banach’s Deep Water (1998), a disturbing painting of a woman with just her head above swirling, yellow, waters. She is looking skywards but we do not know whether she is seeking help or is resigned to her fate. Is the water an allegory for her unconscious dragging her down, sweeping her away on a tide of despair?

Not waving, but drowning.

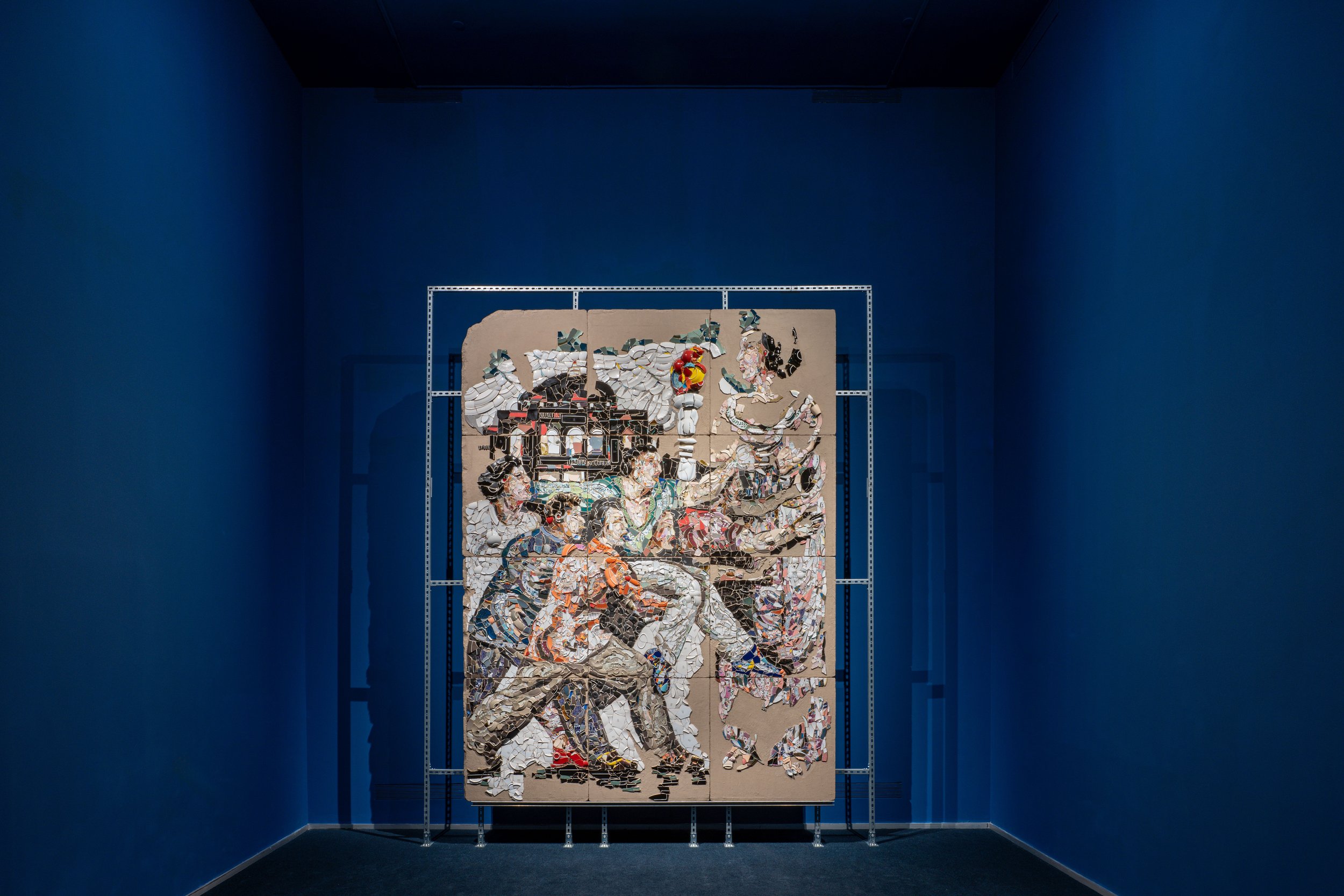

A future generation shines in Kyiv

Discover the power of art - and its importance when a country is threatened.

Read more:

The Blitz, London. May 1941. In one raid 1,436 people were killed and 1,800 seriously injured. Among the scores of buildings destroyed were four galleries of the Royal Academy.

Nonetheless on May 5, the gallery opened its doors to the 173rd Summer Exhibition as ‘a public duty for King and Country.’ In the next three months more than 50,000 art lovers defied the bombs and paid one shilling for the restorative balm of looking at pictures.

Perhaps they had been inspired by the words of enthusiastic water colourist Winston Churchill, who declared: ‘The arts are essential to any complete national life. The State owes it to itself to sustain and encourage them.’

Vladimir Putin - not renowned for any great aesthetic sensibility - understood that. On the eve of the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, he sneered that the country did not have its own culture and threatened to destroy what it did have.

So too did Volodymyr Zelensky who - from a somewhat different perspective - told the audience at the 2022 Venice Biennale: “There are no tyrannies that would not try to limit art, because they can see the power of art.”

The PinchukArtCentre in Kyiv embraces that power. It has defied Russian missile attacks, one of which landed a mere 300 metres from the gallery and knocked out the electricity supply, to stage the Future Generation Art Prize (until January19.

Artists under 35, selected from 12,000 entries from Bangladesh to Norway, from South Africa to China were whittled down to a shortlist of twenty by an international selection committee. To the winner: US$ 100,000.

But, I ask Bjorn Geldhof, Artistic Director of the Centre, shouldn’t the Pinchuk have organised a competition for Ukrainian artists only? More than 100 of them have been killed since the invasion, surely it is their voices and their vision, the Pinchuk should be celebrating?

“Let me answer with not a yes or a no,” he replies. “I think that our role is not only to promote Ukrainian art but very much also to contribute to a country that is open to the world. We always have one Ukrainian artist represented so this also supports our art because we place this artist in the context of 20 of the foremost representatives of their generation globally.

“It also gives people who are still in Ukraine access to that world, to other ways of thinking. It cannot be that we're the only ones who are facing questions, for example, about decolonisation or the environment or violence against women. Just because these issues are made by an overseas artist doesn't mean that the subject is irrelevant to us.”

So who and what did the selection panel choose from the array of video, installation, painting and sculpture? The winner was Ashifka Rahman, from Bangladesh who crafted a dazzling installation of gold filigree strands holding up a platform of green fabric panels. The work, Behula and a Thousand Tales, a reference to a mythical Bengali love story, is embroidered with the delicate handwritten prayers and letters by women who have been trapped in areas of the country blighted by floods but also been the target of repression, violence and rape.

The walls are decorated with an undulating line which represents the riversides she visited when researching the project and interspersed with testimony from women who have been suffering in silence, such as this from Fatima Behu: ‘Dear Behula, With tears streaming down my face I must tell you I am carrying baby conceived from the brutal torture I endured.’

Or this from a mother who fears her 12-year-old daughter has been abducted, assaulted and burned alive. ‘How can I find my beloved daughter in these ashes.How can I gather the broken pieces of my heart.’

It is a work of painful beauty which speaks urgently to the universality of themes discussed by Geldhof.

As does an installation, In Between, by Iraqi Tara Abdullah which stretches like a wall across the narrow entrance to the gallery.

It is made of metal sheets taken from war-torn regions, pock marked with bullet holes, decorated with messages of hope and defiance and which echos to the poignant sound of wailing by Kurdish women. They sing of grief at the loss of loved ones and devastated homes, but they sing also of hope and healing, sentiments which unite the women of Ukraine with those of Kurdistan.

The judges deemed the wall a ‘bold, fearless engagement with the war’ and awarded the 27-year-old US $20,000 as a runner up for work which ‘speaks to women’s role in resistance across different geographies and times.’

In contrast Hira Nabi from Pakistan - another US$20,000 winner - has produced the elegiac film Wild Encounters which warns of the threat to the natural world. Straight roads, sawn-down trees and telecoms towers are destroying his dream world of a mist shrouded forest, its flowers and wildlife. ‘Is no one paying attention?’ he asks and answers his own question: ‘Meanwhile they talk of progress, the fools.’

Porcelain cups are broken into pieces and transformed into expressive mosaics by Egyptian Yasmine El Meleegy’s whose A Cup of Tea with Fathy Mahmoud was inspired after drinking tea from a cup signed by Mahmoud, a well known sculptor in the 1930s and 40s whose relief at Cairo University commemorates the student uprising of 1935–1936 against colonial rule. The mosaics capture that moment but also symbolise how the past can be reimagined to offer hope however broken the present.

Ukrainian Veronica Hapchenko, took inspiration from a harebrained Soviet scheme in the 1930s to divert the flow of rivers from the north to the dry lands of the south. It failed utterly. Her paintings, both muscular and esoteric, conjure up the tremendous energy of the engineers involved in the project against a swirling background which suggests cosmic forces.

Inevitably many of the works are political but Geldhof was pleasantly surprised that the judging panel’s choice of contributions were of a ‘more ephemeral nature’ than he expected and more varied.

One such is by another runner up Taiwan’s Zhang Hang-Xu whose film of his country’s ritual ceremonies creates fantastical landscapes inhabited by spirits, mythological creatures, animals, and plants. Sandra Mujinga, a Congolese-Norwegian, has dreamed up an installation with ghostly hooded figures looming out of a green neon space,

There is however, nothing ephemeral about the wooden sculptures and textiles made by Sinzo Aanza, which react to the exploitation of his country, the Democratic Republic of Congo, during the years of colonial rule.

Millions have died in years of war and civil strife but he argues that merely recording the huge numbers of victims is not enough to explicate fully the horror. He recalls Stalin’s reaction to the deaths of Ukrainians from the famine he himself had engineered in the 1930s to eliminate their independence movement: ‘If one man dies of hunger, it is a tragedy. If millions die, it’s just a statistic.’

Two countries, far apart geographically and ethnically with little in common save the suffering they have endured.

As Inga Lāce, the chief curator at the Almaty Museum of Arts, Kazakhstan, and co-curator of the exhibition, says: "During our conversations with the artists, we asked how... hope can emerge, how movements can form, bringing bodies and energy towards hope, resistance, and ultimately, liberation.”

This future generation is trying to find the answer. Few of them would be aware of the Royal Academy’s decision all those years ago to keep the show alive ‘through recognition that feelings of centredness and belonging, solidity and stability provided by the event had become precious resources’ but they would support the sentiment.

As Ashifka Rahman said when she collected the prize: “This offers a unique platform where voices can be heard openly, allowing us to be both expressive and politically engaged.

“The courage shown by those in Ukraine, who organised this event despite immense challenges, makes this award even more extraordinary. It’s a powerful moment for art and the world.”

When you've seen one cosmonaut you're seen the lot (joke!)

An explosion high in the sky, an object at first just a silver dot comes into view, floating to earth on a parachute, landing with a thud and a cloud of dust.

It’s a capsule from a space craft. There is a rush to open the hatch and out step three cosmonauts.

“My heart gave a skip when I saw that in a TV documentary,” says photographer Andrew McConnell. “It was 2014 and I had just returned from filming the conflict in Gaza where I had witnessed the very worst of humanity, yet here were humans working together and achieving the seemingly impossible. I resolved to go and see it for myself.”

The result, a collection of photographs in his book Some Worlds Have Two Suns (Gost £60). But the result was not what he intended.

Cosmonauts had been blasted into space from a launch pad in Kazakhstan since 1967 to work in the International Space Station. As regular as clockwork three months later they returned to earth in the tiny capsule, a mere 2.2 metres long and just as wide at its maximum, bumping down on the same few square miles of the country’s bleak steppes.

McConnell’s plan was to photograph the faces of the cosmonauts, to take portraits which captured the drama they must have felt working on the space station, to reveal the high emotion that such an adventure aroused. Surely their faces would tell their own story of courage, determination, even bravado, which would reflect the quixotic fact that they had briefly inhabited two worlds.

He quickly found just how mundane space travel could be, at least as far as the cosmonauts were concerned. “They land, they are taken out, plopped down on a chair, handed a phone to call home, given a hat and sunglasses to protect their eyes and then sort of sit there smiling with blank expressions while the press and the space organisations fuss around.

“The fact is,” he laughs. “When you’ve seen one astronaut you’ve seen them all.”

While he pondered what to do a group of villagers from the nearest community came by. He turned his camera towards them and soon found they were more interesting than the cosmonauts. What seemed to him at first to be a ‘boundless void’ was crowded with ‘unexpected details.’

He was to make many trips to the region between 2015 and 2023, often staying in the same village, getting to know the people, their nomadic heritage and their mysteries, which helps explain why the first image in the book is not of a cosmonaut but of an old man standing in a snowy waste, stick in hand, hat and overcoat tightly bound by a broad belt. Behind him, the steppe seems to go on forever, featureless apart from a strip of trees on the horizon separating the dirty white land from the slate of the sky. You can feel the cold.

Turn the page to find a track lined by walls of snow which have been thrown up by the plow as it cleared the way through. A solitary bird perching on a lump of ice emphasises the sheer emptiness of it all. We see a dog ambling through a cemetery towards a distant horizon, made the more desolate because the snow is grey. It has been polluted by the nearby steel works - pictured on another page in all its industrial monstrosity - which blackens the snow as it falls.

But the comfortless mood is cheered by a man standing proudly in his modest kitchen by a table laden with cakes and bread, a lady in the colourful garb of the region poses awkwardly in her home, lads cavort in a river in the summer when the glum monotone of winter is replaced by green fields and blue skies.

But McConnell challenges our perceptions by changing tack. He transports us to a landscape littered with the flotsam and jetsam of space travel, nose cones and abandoned bits of metal. He reminds us what his project was intended to be about with a rocket menacingly poised on the launch pad preparing to take its three passengers into space.

With such contrasting images it’s hard to nail down a theme. Apart from a brief statement at the end of the book by the photographer there is no attempt to provide a context, no picture captions, not even page numbers.

McConnell: “As a press photographer I was always trying to explain everything to the viewer. Here I’d rather they experience it for themselves, bring their own ideas to it.”

What is evident is that the bits and bobs of redundant space machinery play only a small part in McConnell’s observations of this remote world.

A boy in a balaclava and a red coat plays in the yard of his home with his sister. His home is simple, made of concrete with a tin roof and boasting a huge TV satellite dish. In the yard, alongside crates of empty bottles is a nose cone from a capsule. Its use? As a coal store.

In another scene, a girl balances on a discarded shard of space ware while making a fence with a sheet of fibreglass from an abandoned capsule.

Another lad, in grubby anorak and trousers sits rather defiantly on a begrimed armchair surrounded by the detritus of a land fill site. Smoke rises gently by his feet, caused by the permanent fires of rubbish which burn just below the earth. It’s reminiscent of the smoke which billows out at a rocket launch just before take off.

McConnell contrasts a sports hall, shaped like an enormous yurt, in which players plan tactics for a football match with a table of food (for no obvious reason than the delicious symmetry of the fare on display) and with horses trotting in the snow in search of feed past eerily abandoned flats. Two venerable sisters, maybe twins, in similar red coats and gay headgear stand hand in hand.

He is keen to point out the birds nest with four perfect eggs and the tumbleweed he found in a deserted home, shaped in a strangely beautiful filigree.

“Nature at its most sublime is a wondrous thing,” he muses.

The longer he spent in the area, he came to understand that the people were not terribly interested in the space travellers but were nonetheless connected to the ‘strange ritual’ of the landings.

He chanced on a family group gathered on a rock, apparently in prayer or some ancient ritual, and as he photographed the scene the sense of connection between such earthly devotions and the distant world visited by the space travellers was palpable to him.

Again, he found something mystical about the time he was camping in the shadow of ancient tombs when a Soyuz landed nearby. Was it too fanciful to compare the cone-like structure of the tombs with the capsule? While he pondered that, out of the mist rode two men on horseback, drawn, perhaps, to that very spot by the ritual of the inter-galactic ferry service.

“I wanted to reflect the idea of being on the threshold of our world and to that other world up there,” says McConnell. “These descendants of nomads are once again on the edge of a new horizon.”

The folly of it all. And the pain

Dead men hang from tree stumps watched impassively by a lounging soldier; a child weeps as her stricken mother is carried away from the tumult of war; a grieving wife holds the dying husband she cannot bear to let go; a soldier seizes a woman unaware that he is about to be stabbed in the back by a vengeful mother.

Scenes of violence and despair, abject sorrow and pain. These are the images by the Spanish genius Francisco de Goya which the artist Paula Rego hung above her bed. They must have permeated her dreams and certainly influenced her work.

Goya created the etchings towards the end of his life (1746–1828) when he was overwhelmed with despair - and anger - at the political repression and the horrors of conflict which gripped Spain in the early 19th century.

An unusual exhibition at the Holburne Museum in Bath attempts to connect the inspiration Rego drew from the Spaniard’s works in Uncanny Visions: Paula Rego and Francisco de Goya (until January 5) by setting Rego’s series of more than 30 etchings of Nursery Rhymes alongside Goya’s Los disparates (The Follies).

One can certainly agree both artists produced ‘uncanny’ works though the word does not quite do justice to either. Not to the devastating, visual diatribes of Goya nor to Rego’s satirical, fiercely feminist, anti-establishment fantasy world.

Goya drew The Follies between 1815 and 1823, but they were so controversial that they were not published until 1864, sixty years after he sought exile from the convulsions of his home country in Bordeaux, France.

Rego, who died in 2022 aged 87, began work on Nursery Rhymes in 1989, the year after her husband died, partly to entertain her two-year-old granddaughter Carmen who would have been happily unaware of their undercurrents of incest, vanity, violence and even cruelty to children.

She would have been too little to make anything of the boy being beaten in The Old Woman who Lived in a Shoe, unaware of the oddly sinister girl smirking while soldiers gather around the shattered remains of Humpty Dumpty. The dancers in Ring-a- Ring -a’ Roses give no clue that the roses signalled the onset of the bubonic plague and the finale, ‘We all fall down' means death.

In Polly Put the Kettle On Rego portrays herself as Polly serving tea with another woman to soldiers half their size. How could Carmen have known that the soldiers are made of chocolate - and they are, in fact, the tea time treat for Polly and pal?

It’s easy to overlook the horrors in some of these familiar lines. Rego made two images of A Frog He Would A-Wooing Go. One has a splendidly pompous Frog with two ratty chums which would add charm to any children’s book, the other a brutal depiction of three killings which clashes horribly with the rollicking chorus.

But then, as WH Auden said: ‘There are no good books which are only for children.’

Throughout, the influence of illustrators such as John Tenniel, Beatrix Potter, Arthur Rackham, even William Hogarth, is evident but it is with Goya that we are invited to compare Rego’s rhymes and that’s where things get problematic.

Take Three Blind Mice, grotesque creatures more like rats, razor sharp teeth, dead white eyes, attack a woman but she fights back, knives flailing. Alongside is the huge grinning figure of Goya’s The Simpleton. It’s carnival time, he’s playing the castanets and it should be fun, but while he dances two ghostly heads emerge from the shadows. Are they screaming? Shouting? A frightened man hides behind a helpless female figure. That grin is more a demonic grimace.

One of Rego’s more unsettling works is Baa Baa Black Sheep, in which a child seems to be pressing up against the animal - Rego made it a ram - in an embrace. The darkness of the piece is exaggerated because of a mistake in printing which made the etching blacker than planned but, however disturbing it is, Goya’s Unbridled Folly or The Horse Abductor, hung alongside which is altogether more compelling. A horse rears up against a doom laden sky, it is all muscles and wild eyes, a symbol of lust, intent of carrying off a woman, something she seems to quite relish. In the background huge, terrifying rats skulk around, one of which is eating a woman.

Rego represents Lady bird, Ladybird, a poem which might be about the persecution of Catholics in England, with the ladybird fluttering overhead symbolising the Virgin Mary, by staging a stately gavotte danced by elegant ladies and strangely decorous but alarming insects. In Goya’s Exhortations a wild-eyed woman, clearly terrified, is pulled around by flurry of figures, one has three arms, some have two heads, another stands, finger raised in admonition. The curator’s note suggests that the scene is a ‘metaphor for the choice between vice and virtue, lust and chastity’ but the overriding effect is of tumult and terror.

Perhaps it is unfair to compare the two - something that’s hard to avoid given the way the exhibition is organised. Rego was to an extent circumscribed by the theme she chose, though obviously attracted by the subversive undertones of the rhymes.

Goya’s view of the world was sweeping, apocalyptic. In the 22 etchings of The Follies he drew on the deep, sombre corners of his imagination to produce a scathing and haunting denunciation of his homeland.

What to make of the show? It’s a treat to see such rarely shown works and to that extent it’s a an intriguing diversion but putting like with unlike blurs the appreciation of one or the other and suggests that we have to decide between the two?

Of course, both play heavily on the surreal but should we prefer what Auden described as 'A magical convergence: the absurdity of English nonsense illustrated by Rego’s marvellously dark fantastical drawings... Anyone will thrill to these?’

Little Miss Muffet fits that billing. Rego made three versions of the arachnophobic psychodrama, two of which find Miss M distinctly disturbed by the creature but in one she gives the spider quite a kicking. It’s a splendid scene, one of the few in colour, and given a particular piquancy when you realise the creature has her mother’s face. A disturbing aside, and one that acknowledges Rego’s difficult relationship with her mother. Nonetheless, it’s more fun than fearful.

Poor Folly is deemed to be similar to Little Miss Muffet, sharing ‘a sense of impending doom’ which hangs over like Miss Muffet’ with its terrified woman running into a building, a church perhaps. Why does she have two heads? Is she looking to the past and to the future? Are the men behind her a threat? Why is one of them screaming? A gaggle of old women, grim and ghostly lurk, are they urging her on or driving her to a terrible fate?

It could also be an allegory for Spain itself, fleeing from the terrible past of the Peninsular Wars in which more than 200,000 perished but uncertain as to what the future might bring. There really is no comparison to Miss M.

This is a world without pity and little hope. Perhaps Aldous Huxley writing in 1962 captured Goya’s virtuosity as well as any; the way he created the ‘most powerful of commentaries on human crime and madness... uniquely fitted to express that extraordinary mingling of hatred and compassion, despair and sardonic humour, realism and fantasy.’

Beyond the curve

Many artists reprise the same style, similar techniques all their careers. Not Antonio Calderara.

Read more: https://www.theneweuropean.co.uk/antonio-calderara-the-changing-man/

For most of his life Antonio Calderara sought inspiration from the misty shores of Lake Orta, the smallest of Italy’s northern lakes, where houses rise like terracotta ziggurats from the water’s edge, streets are cobbled and narrow, church towers rise above town squares.

It’s tempting at first glance to dismiss the painting as charming, pretty, but that would underestimate their subtle draughtsmanship, the way the planes of shade and light combine to create a sense of mystery, almost one of foreboding.

It was a style which won him years of steady success, but by the time he reached his fifties he announced: ‘In 1958...I drew my last curved line.’

And that was that. No more carefully crafted scenes of squares and quiet streets, instead, horizontal lines, vertical lines, enigmatic square and rectangular shapes often in pastel and invariably set against one dominant colour.

Not so fast. The change was by no means as clear cut as his laconic statement might suggest as an exhibition at the Estorick Gallery, the north London gallery dedicated to 20th century Italian art, demonstrates in Antonio Calderara; A Certain Light (until December 22).

Calderara was born in 1903 in Abbiattegrasso, south west of Milan, before moving to Vacciago on the shore of the lake with his wife Carmela and daughter Gabriella, where he lived for the rest of his life.

He was self taught, abandoning his studies as an engineer in 1925, and was mentored in his early years by Lucio Fontana, who was a family acquaintance, though none of his work reflects the slashed canvases that Fontana made his own, instead some of the early paintings are more reminiscent of Giorgio Morandi, particularly Natura Morta, and Georges Seurat in atmosphere, if not technique.

He was never really famous, he remained a loner whose work was considered by some to be a tad provincial. He did not run with the artistic pack who gathered in Milan and were gripped by the febrile world of Italian art in the post World War One years. Some rejected the violent imagery of Futurism, others embraced the traditionalist styles of the Novocento or gave short shrift to Pittura metafisica (Metaphysical Art), a movement created by Giorgio de Chirico and Carlo Carra.

Rather, Calderara said he owed his greatest influence to the simplicity and subtle light exemplified by the 15th-century Italian painter Piero della Francesca, something that is evident in the earlier works, geometric but with their hard edges softened with pastels of grey, ochre and faded reds.

Take The Market Square in Orta (1929) in which the heat of the day positively bounces off the walls of the buildings, spreading a deep shadow into the square. Black clad figures, a girl in pink, their backs to the viewer, are curiously immobile, keeping their distance - and their secrets. Despite their presence there is strange emptiness about the square.

And again, in a scene across the lake (untitled) to the island of San Giulio which is framed by grey blue mountains, the bulk of the church and campanile are carefully drafted but in the foreground a group of villagers, stand, all with backs to the easel, creating a similar atmosphere of disconnect and mystery.

There are signs of (abstract) things to come with The Factory painted as early as 1932 in which the low lying bulk of the building and the slivers of two smoking chimneys almost disappear into misty nothingness.

By the late Fifties he was finding inspiration in the radical theories causing a stir in the USA by such as Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg and Josef Albers. No doubt he was influenced by Ad Reinhardt, in what might be the rallying call for all abstract artists, who declared in 1962: “The one object of fifty years of abstract art is to present art-as-art and as nothing else…making it…more absolute and more exclusive—non-objective, non-representational, non-figurative, non-imagist, non-expressionist, non-subjective.”

Calderara was particularly impressed by the way Agnes Martin created her grids of horizontal and vertical lines to evoke a world of emotions and possibilities but the most significant influence was Piet Mondrian whose minimalist technique of straight lines and primary colours he first came across in 1954 when aged 51 and whose work inspired his dramatic rejection of the curved line.

To emphasise his progress from figurative to abstract, the curators have hung a winter scene (untitled) from 1951 alongside Painting - Winter (Snow in Vacciago) (1957–58). In the earlier scene the snowy hillside, the dark of the trees, merge with the ice covered lake and the hills beyond. There is something of the abstract about it - it is certainly impressionistic - while in the later version the imagery is reduced to minimalist squares and rectangles of muted blue, grey and brown.

Other paintings are poised on the cusp of abstraction such as Contemplation, (1958) in which a figure, almost christ-like, wreathed in the dull orange of a deep fog, holds what looks like a shovel. In The Bell Tower (1959) the narrow campanile is almost lost in the lines and rectangles and the nuanced pastel shades of the composition. It is framed by walls - a familiar technique of Calderara’s to enhance perspective - and one echoed in many of his abstract works including what was perhaps the first of his unequivocally abstract works Vertical Counterpoint in Red, (1959) in which the merest blush of pink is balanced by two narrow stripes of grey.

A series of untitled paintings using only horizontal bars of colour conjure up his new vision of familiar scenes, the mist and moods of the lake, but the imagery becomes more complex. One Untitled (1960)) has a frame within a frame, the backgrounds are soft, off white, there is one rectangle of pink against grey, alongside another of the lightest grey barely contrasting with the lightest of pinks. In Attraction of Square into Yellow (1967), the greeny-yellow of the canvas is broken only by a tiny green square on the right side.

Some of these, often enigmatic, images invite the viewer in. Some coax, all challenge. Space Light (1961–62) is a deep, deep red. It demands you peer into its depths, where, what seems to be a solid mass of colour, almost conceals oblongs of reds in different, intense shades.

It is impossible not to be drawn in by Parallel Encounter in a Unit of Light (1960), its powerful black broken by two sets of grey in different strengths which perhaps reflects the intimations of death he must have felt after suffering heart attacks and the grief he still felt at the death of his daughter in 1944. So strong was his pain at her death, he ‘updated’ the portrait which hangs in the exhibition several times long after she had gone.

These paintings fulfil Calderara’s desire ‘to paint the void that contains completeness, silence and light. I would like to paint the infinite’ and none does that with greater intensity than Constellation painted in 1969. Pitch black with tiny grey and even blacker squares there is something Rothko-esque about energy it radiates with its luminosity and emotional pull.

As he wrote to a critic friend: ‘Structure and reason should never overshadow the emotion that I like to define as ‘poetry.’’

Give the man a break!

One of Norway’s grandest painters, Adelsteen Norman deserves better as the European Capital of Culture unwittingly shows.

Read more:

All that glisters...

The work of Anna-Eva Bergman was a revelation of glowing, pulsating colour

Read more:

https://www.theneweuropean.co.uk/the-gold-and-silver-medallist

Impressions, then and now

I never got an explanation why they decided to do this project but it is a delight.

What the end of the world looks like

For those world leaders, and their followers, who talk casually of nuclear war, here’s a reminder of what will happen. Read more: